Whakarongo ki te Whenua

Elle Loui August, Madison Kelly, and Rachel Shearer

Ko te Rāapa, te 4 o Mahuru, 2024

The following conversation connects three places; Rachel in her studio in Tāmaki Mākaurau, Madison sheltering from high spring winds on the streets of Naarm, and Elle Loui as silent listening partner at Ōhinetū Point, Ōtākou. It was recorded via zoom, transcribed, and edited via email, and continues kanohi-ki-te-kanohi kōrero from Mahuru 2023 in and around Ōtepoti Dunedin. Where reo Māori appears in the printed text, the spoken mita from the original conversation is preserved, moving fluidly between Te Ika-a-Māui and Kāi Tahu dialects.

Rachel Shearer

Maybe we should start with, how do you listen to the whenua? Because, it's really interesting what you were saying, Madison, about being there in Australia, being in that space.

Madison Kelly

The most interesting thing is that as soon as I'm somewhere else as manuhiri, I realise how differently I listen to whenua, specifically whenua Māori; ways of being out in the field at home on the whenua that I've sort of subsumed into my practice. I have realised that when I'm at home, I'm listening for things that I am hoping to recognise, because those will help me understand where I'm sitting in that whakapapa, whether that's certain manu or even winds, you know—thinking about the Haupapa glacier work that you collaborated on. I'm almost listening for familiar faces to ground me. Then I have more space to feel what’s unknown, that I can come to learn. Whereas here in Te Ao Moemoeā, on country in the bush every day, I have no entry points whatsoever.1

I have found myself shifting the way I sit in space, and even the types of things that I have been recording. I started giving myself tools to speak something into the place so that I could listen to that conversational relationship instead. I've been making little pūoro out of really rudimentary materials, like cardboard and twine, to speak with, since I don't have a language that whenua knows.

I've been thinking a lot about how language is derived out of land. When you're in Aotearoa, on tūrangawaewae, you can mihi everything. I've experienced two very different versions of listening in the last few months. How is it for you, working? I’m thinking especially of your work with pounamu, something so deep in time, and processes that extend in a way that feels quite distant from what our ears could even register.

RS

Yeah, that's right, for me part of it is to do with my position of having Māori whakapapa, but also being Pākehā growing up in Pākehā culture, those colonisation processes did their job well. In dealing with my colonised brain and trying to reconnect with my Māori whakapapa, I have found listening to the whenua as a way to reconnect. There's also listening to ideas about the whenua. In terms of pounamu, and this idea of pounamu becoming crystal, there’s a bit of a story behind that. A woman who has the same name as one of my tīpuna, had talked to me about the sound of the patupaiarehe, that their songs sounded like pounamu becoming crystal. That idea went bong inside my head, something about it struck very deeply with my connection to te ao Māori, through my grandfather. It felt like a tohu. I recognise echoes of te ao Māori, rather than having a direct experience of growing up within the culture. I guess this is also a reflection of my age as well, you know, my generation and what was happening in terms of te ao Māori in the wider culture of Aotearoa when I was growing up.

MK

Yeah, absolutely. I'm really interested in what you've just said, about listening to ways people talk as a way of listening to whenua, because you're seeing how it's being shaped. Do you think you've noticed shifts? My time here in Australia, you overhear a lot. Walking as a stranger, and just hearing snippets of conversation, it gives you so much information about how people are regarding land, and movements like Land Back. I wonder, have you noticed shifts in that more casual kōrero that floats around day to day?

RS

Yeah, definitely things have shifted in many ways but that also may be because I’m listening differently. There's that listening to the whenua through the kōrero of other people, and less casually talking to those closer to the source. And reconnecting with our tūrangawaewae of our Māori tīpuna. Thinking about pounamu becoming crystal was like that for me, it felt like a link to the tīpuna, and listening to them—the more you listen, the more you hear.

MK

I feel similar, especially when I'm in ngahere, just because I spend so much time working in those spaces as a guide, but even when I first started doing that type of work, bird calls were the first way that I felt like I was being guided. Even if I didn't feel like I understood the full context of a particular whenua, you hear certain calls and voices, and even things like the sounds of certain trees moving, and they’re reminders of a really continuous time. It’s a lot easier to feel present back into whakapapa, and also forwards into whakapapa, and you think, oh, these sounds and these conversations have just been continuing, and they will do, you know, they will continue onwards. It’s easier to step into what I think is a more full feeling of whakapapa, a very continuous backwards and forwards. It’s very calming to get into a space where you feel like you can actually listen for those things properly.

RS

That's right, sensing space is also listening to all of that dynamic, situational, everything that's going on and changing. And field recording, you listen differently with field recordings, do you find?

MK

I mean, it's similar to what just happened in this kōrero. You have to, at some point, decide to start recording. I always find it quite funny, trying to recognise the point where I hear a kind of trigger, and I've got to assess what I'm actually going to be recording, and then push record, and then see how long it goes for. As soon as you start making those decisions, it's curatorial, in a way, and I do think it's a funny relationship, but it's also something that I rely on very heavily once I leave the space. It always feels a little bit like it's falling short when I'm there, but as an archive, it helps access more of that sensing feeling.

I think my relationship to field recording isn't necessarily one-to-one, it's like using the recording to supplement that sensing experience, so that later on, I can think on what senses might be useful for other people to also access that whakapapa. But it always feels very different before and after. It feels like I've altered something by doing it. I suppose it's also like speaking something into that space, or the idea of taking something away, like taking photographs, or taking slices out of the air. I always try to make sure that it feels reciprocal, you know, even if that's months down the line, in terms of what materials I end up using, or how things get installed. I always want access to that type of data to feel reciprocal at some point, with where I've taken it from.

Pictured: Rachel field recording Haupapa (Tasman) Glacier Lake, 2023.

Photograph by Janine Randerson

RS

Yeah, being mindful of the tikanga of what's involved, being mindful of the agency of what you're listening to, how you treat that material, what reciprocity in that moment requires. When we were recording down at Haupapa, kaikōrero Ron Bull—who would be a whanaunga of yours—offered karakia and kōrero to that space for the recordings that we were going to take. There was also the follow up protocol of what we did with the recordings afterwards, how they might be replayed in spaces, or used.

MK

I’m always grateful for the function that karakia has with any kind of harvesting—in a sense of wairua, but also in a really practical way of regulating breath, and regulating thought, and settling yourself and your body, and that action of speaking things out, and having rhythm in the site. That applies to all kinds of cultural use, I suppose. If I think about field recording, or ways of exploring sensory aspects of a whenua, it's using tools like karakia. Then in turn when you're making work, if that has its own raki and papa, and qualities of sound, that's kind of like the call back. It's another version of a karakia that you can put into the space, so that when people come in, they're not feeling thrown into it. I think a lot about rhythm, and how when you're building installations, or you're building spaces that welcome people into those areas, or that whenua, what can you use to ground the space through breath, or pulses, the same way that we know that karakia and those rhythms work in the field?

RS

Yeah, absolutely. I think, as I've developed with my field recording practice and introduced karakia as part of it, I think my recordings are much better because of it.

MK

That's great.

RS

But I was interested in something you were just saying about rhythm, because often I think of you as a rhythmic person, whereas I often find I'm kind of sifting through the air, it's like I'm the Rangi, you're the Papa. Not always, but in terms of some of the bodies of work that we've done.

MK

Yeah, absolutely. I have been thinking about that a lot recently, how much of my work is using rhythm to ground space, and then the Raki is whatever's pushed out into the air during that percussive process. It's probably a little bit of bias, because it's one of the works of yours that I've seen in person, and felt in person most recently, but the Haupapa work, so much about that, even the way that light was working, you know, that's so spatial, and so reliant on this feeling of air, and the feeling of Raki. I really associate that with your work.

We had touched on this briefly in a different conversation in person, but I always think about what the responsibility is of assigning different quantifiers, or different categories to things that we've recorded, to things that we find, or things that we're able to hear. How do we decide how to present that to other people? More specifically with that Haupapa work, you know, there's decisions that have to be made about what kinds of sounds, and what kinds of audio are being produced for different data coming from the weather stations.

I just wonder if you have any thoughts on that process, or the responsibility of that?

RS

In that situation, that was a collaboration, so it was about responding to everybody that was involved—the kōrero that Ron brought with him as tangata whenua from the area, the work that Janine [Randerson] did with the moving image, but also the programming that Stefan [Marks] did translating the weather data. Respecting the mana of everybody's contribution—the mana of the kōrero of the area, but also, the mana of the data that the weather station was sending. As a tool, the idea was to create immersive situations where people could experience the space and its real-time changes in some way, drawing attention to climate crisis while allowing Haupapa to keep their secrets.

I used to worry a lot about creative practice decisions, whereas now I find that I just try and be a bit more intuitive, find the things that jump out at me and try not to second guess, trust my response to the atmosphere or wairua that is emerging, tinker until it makes me feel a certain way. I do notice that I've gone through periods of being drawn to different features as well, so I've had quite a long period of time where I've been drawn to the shifts in higher audible frequencies, hisses of varying textures.

I was also going to say about Haupapa, those hydrophone recordings, the beautiful booms and cracks and glistenings, which sounds like glacier collapse, but it's telling a story that's not mine.

MK

I'm interested in two things that came from your kōrero just now. One is the idea of keeping secrets, and letting certain kōrero stay in the site, and stay protected in some way, but also that process of intuiting and figuring out what's right through an embodied knowledge. They intersect. It's only possible to make decisions about what's not going to be shared, and it's only possible to get to that point of embodied knowledge by being there.

It’s a real koha getting to spend time in a site to absorb as much as possible, so that later some of those decisions are just sitting inside of your body in a very hauora kind of way. I've found myself falling into that decision-making mindset of recognising things in the body. I'm not trying to analyse the exact scale of something or tune something in a particular way anymore. It's more knowing what feels accurate in my body to the place, and knowing that there are certain frequencies that maybe I'm not even registering, or tactile experiences that are connected to something I experienced, but don't have to pin it all down immediately. I think if we spend enough time in that place, in our place, we kind of get a sense for what should and shouldn't be taken out.

RS

Yeah.

MK

I’ve been lucky to spend time in some really incredible sites in Australia, and for a lot of it I've been in certain areas knowing that I won't take or share anything from there directly. Maybe it's sitting in a very tense way, or it's sitting around me. It’s actually incredible that there can be all that information that remains closed and safe, and working around that still tells you a lot about the encounter.

RS

It's a part of my thinking around this work, because so often, even within Aotearoa, I'm manuhiri, I'm out of my area. The responsibility of approaching that, accepting what gets revealed is what is meant for the work, and being aware of those wider issues around the intellectual property of the whenua.

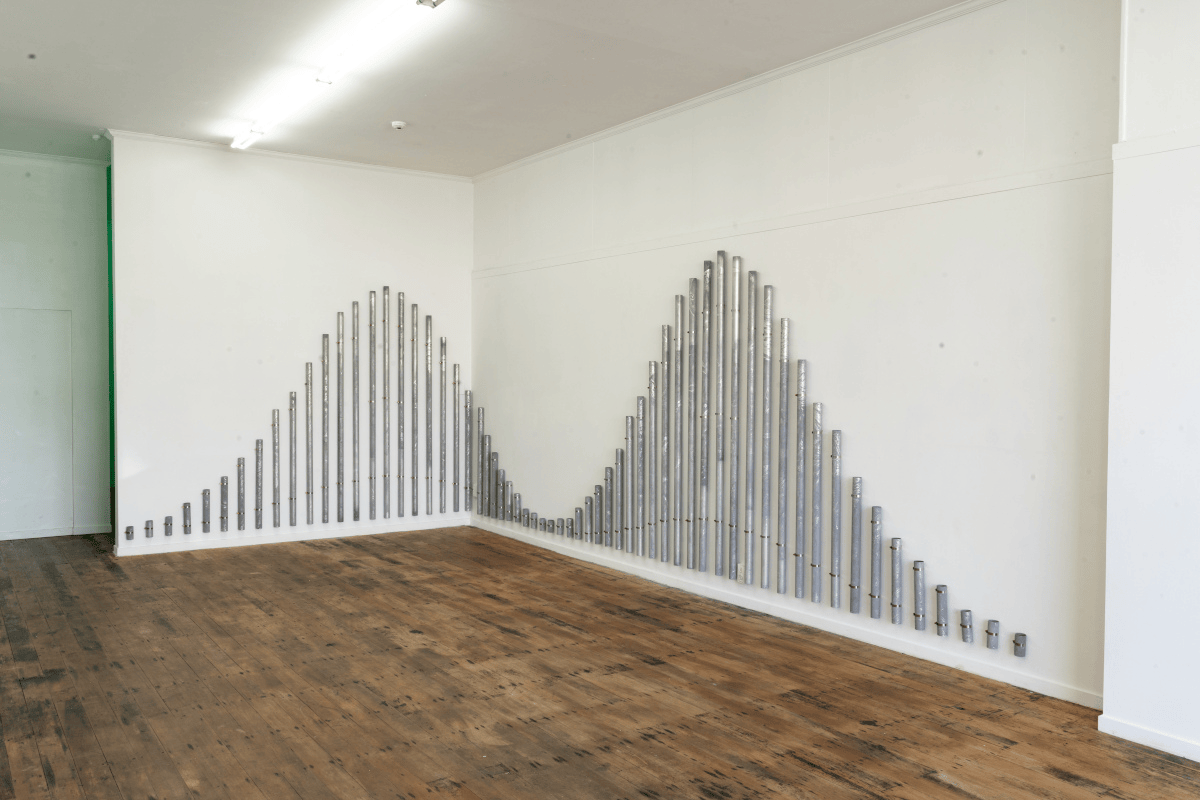

Madison, I also wonder, because I've seen work you've done that speaks to the natural world in various ways, and are presented in different forms—like the work I saw at the Dunedin Public Art Gallery, where you cast items, and the pipes that echoed the shoreline [at Blue Oyster Gallery]—if you wanted to talk a little bit more around field recordings, but also your relation to those other ways of translating and creating spaces that relate to the whenua.

Pictured: toko by and by, Madison Kelly, Blue Oyster Art Project Space, 2022–23.

Photograph by Blue Oyster Art Project Space

MK

My entry points into a site are using field recording as a way to accumulate as many intersections as possible. From there, I'm mostly thinking about surface and also the idea of vessels. Everything has an inherent resonance and a way that they're going to emit tone, and you know, I am trying to find what kind of material and what kind of form will be the best, the most accurate vessel to speak outwards. In the last year or so, a lot of it has been really, really informed by those concepts that are used in taoka pūoro of Raki and Papa.

I've been thinking about this a lot—all of a sudden you get these little convergences where you think, oh my god, there's one form or one action that holds those encounters or experiences on the site completely. I don't always know what that's going to be. That work from Blue Oyster was the tidal chart, which in some ways to me felt almost too obvious, because it's literally the data of the tide. The tide has its heights, and it has passage of time. A lot of my time around Whaka Oho Rahi (Broad Bay), I was also swimming a lot, and feeling the waves against my hands. You know when you're pushing against things, you feel the pulse of things. I was thinking about really simple ways that we feel rhythm in our bodies, because I suppose that was one of the first works where I really wanted to invite people in to feel out those rhythms. That idea of running your hands over a fence line, or pushing your hand against currents as you're treading water. I wanted to have people walk and feel the pulse shifting over time—like dragging a stick along a picket fence. So that literal wavelength pipe shape ended up as the physical form, but also as a tohu that made sense in lots of ways to me, and I think it really felt a lot like whakapapa.

I'm interested in space that can be navigable. By the time I get to the point of installing, I always want it to be navigated, rather than a single encounter. That seems to be really important. I think that's a key difference to when I'm recording or gathering information or just trying to meet in this particular place, I feel like I'm really staying in one place the whole time. Almost like an experimental control. Stay in one place and just see what comes my way. By the time I'm in a space or building a space for other people, I really want them to be able to move and discover intersections.

I don't know if that answers your question or not, but that's what I've been thinking about.

RS

Yeah, absolutely, and I was also thinking of the beautiful…is it…bronze?

MK

Yeah, the lizards!

RS

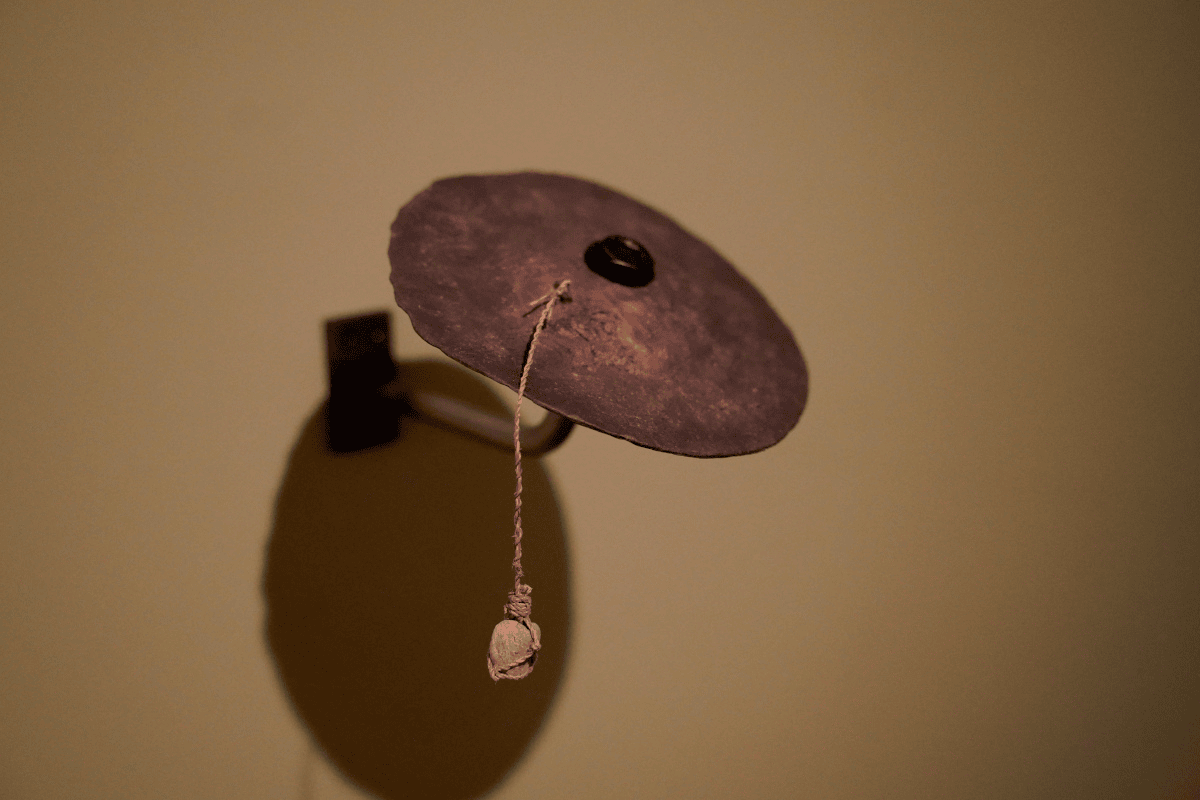

Yeah, the lizards and the different percussive instruments that you created in terms of vessels, is that relevant to that too?

Pictured: TAUTIAKI HAPTIC, Madison Kelly, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, 2023.

Photograph by Madison Kelly

MK

Yeah, absolutely. I love the softness of wax, the malleability of it and the way it's really haptic. That lizard show, a lot of it was about the way that mokomoko regulate their whenua, you know, their roles as kaitiaki. They sense things in the environment that hopefully we can then pick up from them. They traverse between different ao, through the underworld and then above, and it's a very sensitive thing. I was really interested in these small sensitivities, so a lot of those castings were very small and contained and kind of pinging out from different zones, and sometimes you wouldn't always see what was making a certain sound, there might be someone behind another wall activating it. The bronze casting I just love because it keeps, you know, all the fingerprints and all these little tactile decisions, so yeah, I'm quite obsessed with how much information is kept through touch when you're doing that sort of casting. That felt really important for that work, just because of how closely enmeshed our lizards, our native lizards are, through touch and through that really close contact, literally sandwiched between our rākau, our pōhatu and underground. They're always deeply touching in between things, so it just felt correct.

RS

That touches on something I was thinking about in terms of collecting data through our senses and our methods of echoing that data.

MK

I'm wondering, for you, your practice extends so far, and you've worked in so many different contexts. I wonder, do you think there's parts of your sensory experience that have shifted just by having that as a practice?

I'm always really interested in what happens when people are constantly trying to attune themselves to places, will they start changing their ways of listening? For example I think my vision is fine, but sometimes I rely on it a lot less and that reliance changes quite a lot from place to place.

I'm curious if you have any whakaaro on how things feel in your body over time?

RS

I think as I've got older, I've become more relaxed with the whole process. That makes it easier to be more intuitive. And it's just practice, the more I tune in to finding that feeling, the easier it is to go there.

MK

And things like karakia, are there new tools or new tikaka that you follow that you think are supporting your ability to tune in?

RS

Recently I've been learning some basic karanga forms so that I can karanga to the taiao. And, you know, with that whole kōrero around karanga, you karanga out to the universe, and it speaks back to you in some way. So that's a new practice to me. I guess things can take a bit of time, so we'll see what starts coming back.

MK

Oh, yeah, I'd be excited to see what the response might be.

RS

Yeah, but you know, simple forms of calling out. How about you?

MK

I have been, especially here, I have been using pūoro a lot more. And recently I was lucky to attend a big wānaka out at Puketeraki with Ruby Solly and Alistair Fraser. That was really beautiful. It was based on literally just trying and testing and removing that intimidation factor. Something that has stuck with me a lot from Ruby's kōrero, but also from our friend Rua McCallum as well, who supported and informed a lot of that contemporary pūoro space, the idea of pre-reo, the tools that we have forged for ourselves, that are ways of speaking through pure vibration into space.

Like I said, that oro approach has helped me introduce myself to a place or helped me gift something, even if I'm not quite sure what. I've been really interested in using specifically percussive pūoro, like tumutumu, stones. I've always been really interested in pōhatu and the way that they're inherently connected to rhythm and to grounding. But also other taoka pūoro like the porotiti and the pūrerehua, these tools that we have for moving air and for humming and breath.

With porotiti there’s that pull and tension release like in your body, it breathes with you. I think that's been really useful to me and it's shifted my ability to enter into new spaces. But I only really started doing that in a very concentrated way once I was on country, not on whenua anymore.

Even in the place I stayed (Bundanon) there's multiple language groups in that area. I didn't have a way to say, oh kia ora! I would walk into the bush and see an echidna and my instinct was to chuck a kia ora its way, and that felt off. In a deep time way, that particular mihi doesn’t reflect or absorb the same on country as it does on whenua. So I've been thinking about ways of still putting sound forth and speaking into place without relying on just myself to do that, thinking about our tools that we've already developed.

There are really beautiful incentives with pūoro, that you have to be listening well in order to know what to put out in return.

So it can be very good as an introduction, but it's also a nice way to feel like you can converse. There's this amazing lyrebird who was around on site, well actually there was a pair of them. Sometimes I would go out and hear the male really testing the full suite of all of his different calls. Every now and then I would think, I'll throw something back at him.

I wasn't there for long enough for him to pick a lot of it up, but it felt like a really nice way to speak back and forth. So that's been a big one for me at the moment, really investing more in taoka pūoro and the speaking role that it plays as well as the musical role.

RS

I learnt the flute when I was younger and I've got a kōauau that I was gifted-

MK

Oh wow.

RS

…which I play but I haven't gone deep yet, and I've grown some gourds, so I'm going to cut the end off to make a hue puruwai because I love that boom sound.

MK

Oh, absolutely.

RS

Coming back to the rangi and the air and the hau, I really love the breath that comes through the kōauau. That's something I come back to again and again in recordings, making tone beds that are animated with breath.

I was just having another look at Anne Salmond’s book, Tears of Rangi, where she talks about hau as very similar to how I might understand mauri. It made me think about the way that I understand mauri in the context of listening to the whenua, being in spaces listening to all the entities out there, mana ki te mana, mauri ki te mauri. But thinking about the idea of hau, which came up with Haupapa as well, trying to deepen my understanding of the relationship and differentiations between mauri and hau, which I'm not fully clear on, but there is something about hau that keeps coming up.

MK

Wow.

RS

Also, as you know, recording the wind is really, really difficult.

MK

Yeah I've been thinking about how you've been doing that this whole time. In Naarm right now they've got famously very, very high winds at the moment. They're still not as high as some Wellington winds, but for this area, it's quite notable that you can see the way that the trees react and how much falls off the rākau—all these different kinds of play when high winds pick up. But I've never tried to actively record wind.

It's always something that ends up there. Do you know what I mean? It's a fun voice that shows up whether you're thinking about it or not.

I’m wondering about white noise. I really like recording things on my phone because it’s kind of a crappy recording instrument, but it gives you this tone of everything melded together. It's less about being able to pick out individual things, and more like, oh, what's this collective little fuzzy version of it?

But I wonder about actual tones in the wind. Are there things that to you need to be really clear? What's your relationship to clarity versus inherent quality of the recording that you get through things like wind interference and buffeting, things being blown out?

RS

Yeah, often it’s just trying not to let the wind blow out the recording. I totally embrace lo-fi recordings and recognise how they can often be better than hi-fi recordings. I mean, there's definitely better technicians, but for me it’s just trying to find a way to record some feature that presents itself in a space that might effectively translate somehow.

Often I'll hear beautiful winds, and it’s coloured by whatever is in the space, the vegetation, structures, there's nothing better than a little bit of a whistling around the back of a house as the wind comes through. So, sometimes it's just really elusive, you might capture the sound in a recording but the recording doesn’t work for whatever reason. So it becomes something to perhaps reconstruct from memory.

I do have this wonderful sound, which I constantly reconstruct in my head and in sound practice, from when I visited Hawaii a long time ago, a year before my daughter was born. She's 20 now. And it was too hot and the wind was up where I was wanting to record. I went with a good friend of mine who develops education resources for kura kaupapa. This trip was about collecting resources to tell a story of Ngātoroirangi’s relationship to his volcanic sisters in Hawaiki.

And so on the Big Island, we met with tangata whenua and I asked if there was anywhere I shouldn't go? And Kekuhi said “Well, if your recording equipment doesn't work, then you're probably not meant to record it.” So we walked all over these hot black shiny rocks and got to where lava was slowly oozing out of the ground. And it had this most beautiful sound, the rocks heated up until there was this subtle crack sound and there was a hiss as the hot lava oozed. It felt like such primal sound, this crack and hiss. And I tried to record it but it was too hot to get close, and there were some other tourists talking and making sounds, and there was lots of wind and there's just nothing I can do with the recording. But it's a sound that I've thought about and tried to replicate over and over.

Some wind is a bit like that, I think.

MK

Yeah.

RS

It's not to be captured, but can be recreated as some kind of homage.

MK

That's beautiful. Tributes.

RS

Tributes.

Pictured: Tohu!Karaka!Braid!, Madison Kelly, Te Puna o Waiwhetū Christchurch Art Gallery, 2023.

Photograph by Te Puna o Waiwhetū Christchurch Art Gallery

Pictured: Tohu!Karaka!Braid!, Madison Kelly, Te Puna o Waiwhetū Christchurch Art Gallery, 2023.

Photograph by Te Puna o Waiwhetū Christchurch Art Gallery

MK

And pūrākau as well, like sharing story.

It makes me think of working in spaces where there's an opportunity for sound design. Really thinking about how sound is cutting through space, or the direction of sound and how people encounter that as visitors. But, you know, I think there's lots of connections to carving—and this is not a unique thought—but you know, ways of carving out space.

It reminds me of whare tipuna and ways of holding forms and stories through that absence and presence, the rising and fall of different things. That always feels very relevant when it comes to actually installing. Who is projecting outwards and also where are the little recesses that people can rest in?

RS

Yeah, nice.

MK

I think that lizard show at DPAG, that was the first time that I'd had the resources to build walls. But it really shifted my feelings around spaces for people to move, but also, if someone stayed in one place. What might reach them and what won't? The decision around what will be moved through, I think, is one of the most amazing parts of sound and creating sound for other people. It's so nice to build space like that.

RS

I love that idea, what we call into a space, you know, you craft the space with an idea, and yet the things that come to it because of what you made create something else. And that brings me to another question, which, I don't know if we leave this in the interview, but why do we do this? Putting these things into the context of exhibition spaces? Have you got any thoughts around that?

Recording of the work Tohu!Karaka!Braid! by Madison Kelly being played, Te Puna o Waiwhetū Christchurch Art Gallery, 2023.

MK

It's an interesting predicament. I always try to follow my intuition around what could be really rewarding for other people, or what would be interesting.

But at the end of the day, there is a bit of self-fulfilment in there as well. Sometimes I will be really lucky to engage with certain sites and learn in a way that I am aware is inaccessible to other people. I even think about members of my whānau who don't live in Te Waipounamu, or maybe they feel like they don't have a right to navigate some of those spaces, especially in a te ao Māori sense.

I'm mostly interested in access. I'm really interested in how whakapapa can be accessed in a way that is a bit more in the body. That access and sharing is really important to me.

I think that's part of that reciprocal process. I feel like in order to complete the circle of getting to meet and learn in certain spaces, I have to then give something back. But I do find that changes my decision-making about where I show that type of work.

I often feel compelled to show work in a place that's at least as close as possible to where I've been recording. There's certain work that is related to the wider Tū te Rakiwhānoa region around Canterbury that I only feel happy if it's shown in Canterbury, because I want the people of that place to encounter it and to have some feeling of closeness.

My feelings on that have changed a little bit being in Australia, but I am really interested in proximity and helping people feel more connected to things that are closer to them than they think.

It's very driven by that sharing element. I come from a big long line of educators and people that love to talk. Maybe I'm just trying to make work that can be chatting with people and sharing things, keeping things open for others.

What about yourself?

Pictured: Rachel performing live in and with Lava Cave, Tāmaki Makaurau, 2012.

Photograph by Kirsty Cameron

RS

Yeah, I relate to a lot of what you say. In terms of self-fulfilment, I know with lots of creative people, whatever level that you're working, there's a sense of, if you didn't have a way of creatively expressing, you'd probably get quite depressed.

And with listening to the whenua and connecting to te ao Māori through that listening, well that feels a little bit fragile, do you know what I mean? Because for me, it's a learning process and a connection, reconnection. Sometimes I feel like, oh gosh, who am I to be putting this out there, you know what I mean? But at the same time, having to tell myself to be brave and just be part of the conversation and be prepared to learn as I go.

But also, I really appreciate it when I see your work and others that might be interested in a similar conversation. So then it reminds me, oh, well, I should keep doing this because maybe other people are interested in engaging in this conversation with me.

MK

Oh, completely. That's whakapapa playing out, you know, no one's isolated and no one sort of expression is in a vacuum. We need lots of people to be responding and inviting to share in it in order to sustain. Turumeke Harrington had a really amazing project at Blue Oyster a while ago, and as part of that project she was able to commission a taoka for her whānau, which holds lots of kōrero about the making of art as a multi-generational taoka-forming process.

It makes me happy knowing that sharing kōrero from whenua and whakapapa is like the start of some kind of new taoka that people can sit with and hold on to. Absolutely. That's the goal at least, I don't know. It feels immense, but it's a nice thing to constantly work towards and maybe never actually fulfil, but it's a good goal.

RS

Yeah, that's right. And that brings me to the core of working with this kind of listening to the whenua is not just a Māori thing, it's for everyone, that connective, relational thinking, tuning into your environment and what's around you in the space that you're in, as a real and political way forward.

MK

It is political to use your time and your skills to make the whenua really, really present. Any work that's really trying to forefront whakapapa and whenua and Raki and Papa, that's a really deliberate choice to evoke it in a way that is very hard to ignore. When you're thinking about sensory knowledge and things that are experiential in the body, no matter who's visiting, they’ll be privy to that in some way, and they're going to have that whenua’s kōrero seeping in. There's a lot of potential for all of that.

People are moved constantly by sensory experience in ways that they won't necessarily have words for. If you can tie those experiences to the personhood of whenua and the identity of whenua and the life of it, then I think that's also a very strong thing to strive for.

Notes

1

At the time of recording, Madison had just spent a month at the Bundanon Arts Centre in NSW Australia, as the inaugural McCahon House Fellow.

Rachel Shearer (Rongowhakaata, Te Aitanga a Māhaki, Pākehā), based in Tāmaki Makaurau, explores listening to the energies of the earth and the materiality of sound through Western and Māori philosophies and technologies. Experimental music, field recordings, embodied listening, installation, sound/spatial design, moving image, and writing are all variously engaged towards this kaupapa.

Madison Kelly (Kāi Tahu, Kāti Māmoe, Pākehā) is an Ōtepoti-based artist, musician, and kaiārahi at Te Korowai o Mihiwaka, Orokonui Ecosanctuary. Grounded in Kāitahutaka, their practice explores field research, mark making, and percussion as kindred interfaces for the learning and sharing of multispecies whakapapa.

Elle Loui August (Pākehā) is a writer, curator, and researcher in Art History based in Ōtepoti. Her exhibition-making and publishing centres the knowledge practices of artists, writers, and critical thinkers from Aotearoa me Te Waipounamu with an emphasis on experimental and expanded frameworks linking artworks and ideas to history and place.