Transformations of Abandoned Spaces

Zak Argabrite

Story

When I was 10 years old my Dad had a job working for the City Government of Louisville, Kentucky. Part of the job involved inspecting buildings and assessing whether they might be good candidates for historic preservation status. He brought me along to several of these visits—a veteran’s hospital on the edge of downtown situated in a noisy spiral of elevated highway ramps; a house on a former tobacco farm outside of the city that had recently become city land; a shotgun house with the roof caving in. As my Dad worked, I would take in the curiosities that filled the space. I would try and piece together narratives and ask questions about the spaces and what was in them. What is this? What is this doing here? Is that what I think it is? How did that happen? What is this for? Who did that? Why would someone leave this here? Who lived here? Who worked here? Why did they leave?

I have often thought about these experiences since, and observed the relationships abandoned spaces have to other topics: architecture, home, community, waste, land, the natural world, and regrowth. As a musician I am also curious about the acoustics of these spaces and the relationships they have with sound. This curiosity has led me to involve abandoned spaces in my creative projects. My creative endeavours and other experiences with these spaces have in turn helped me develop a deeper understanding of not just abandoned spaces but a broad range of other subject matter including instruments, materials, and sound. However, before diving into these ideas, I first want to break down what I mean by “space” and “abandoned” when talking about abandoned spaces.

– Space

Among the many topics surrounding “space,” I find abandoned spaces interesting because through my experiences with them I have noticed special transformative qualities. The physical shape of these spaces provides an initial example of this transformation. When I imagine an abandoned space, I am typically thinking of architectural ones, spaces that are enclosed in shape—having things like walls, floors, and ceilings. While being enclosed is typical of these spaces, there are exceptions which I think say something unique about abandoned spaces. For one, commonly enclosed spaces such as buildings and other structures are, in some cases, not fully enclosed (such as an outdoor theatre) or feature liminal areas between the enclosed and non-enclosed (such as a loading dock). While those exceptions are also true for occupied (non-abandoned) spaces, the category of abandoned spaces frequently also include formerly enclosed spaces—ones that used to be enclosed but are now less so. For these formerly enclosed spaces, holes have emerged. Architects Joshua Comaroff and Ong Ker-Shing describe this phenomenon as follows (Horror in Architecture, 2013, p.122):

The hole suggests an inability to enforce the order or territoriality of the body. It may operate independently of the will of its host—performing strange functions, allowing traffic in or out. The breach is a threshold of momentous, and possibly dangerous, agency.

Pictured: Photograph from interior of cold storage facility in Kentucky, 2016.

Photograph by Zak Argabrite

I interpret Comaroff and Ker-Shing’s description as meaning that these perforations themselves make decisions; specifically, decisions that conflict with the interests of the enclosures they open. I appreciate the idea of agency in this description, because I think it supports the idea of these spaces having the potential to change or transform. What if the holes that define formerly enclosed spaces are actually a part of, and not independent of the space they emerge in? Perhaps the holes are signs of the space itself having agency, willingness, or even a desire to be transformative in terms of physical form. In other words, perhaps abandoned spaces want to change how they are shaped or situated, and over time they do. Of course, abandonment itself could also be described as an external force—something that happens to a space. If I am imagining spaces as having wants, I must also consider that being abandoned could easily not be what it wants. After all, do buildings and spaces not have important relationships with caretakers? That being said, consider the fact that while spaces might want to be cared for, they might not want to be maintained in perpetuity, forced to perform a certain functionality into infinity. Like a person, they might grow old and need rest as a form of care. They might need to return to the natural world. Whichever way an abandoned space’s agency is aligned, they are spaces which demonstrate a specific dynamic quality. When left unmaintained, spaces transform. This is something that makes abandoned spaces unique among other types of spaces. They are transformative spaces, somewhere along a journey from closed to open.

I have been talking about shape as an introductory example of how spaces can be transformative. However, the uniqueness of abandoned spaces can also be discussed beyond how they are shaped. I understand place or a sense of place to be an important quality of virtually all spaces. Place relates to a space’s identity, what characterizes it, the multiple narratives and stories that surround it, how it is thought of, what it is associated with, and who or what it relates to. I believe the sense of place of an abandoned space offers particularly interesting considerations, because of how the sense of a place transforms dramatically after it is abandoned.

Abandoned —

In order to talk about how the sense of a place changes with abandonment, I need to be specific about what I mean by an abandoned space: a space that is no longer used—space that is given up on, wasted, discarded.

To me, through the process of abandonment, there is a loss of importance, or at least a transformation of what is important about it. A memory of visiting an abandoned industrial refrigeration facility on a hot summer day provides an example of this transformation of importance. In it, there were multiple floors of large rooms, which acted as refrigerators—important for keeping things cold and preserved. However, when I visited these rooms, the heat and emptiness of the rooms made obvious to me the transformation that the space had undergone. There was a sense of loss, and signs that things were missing or out of place. Yet, the way every bit of wall was adorned with graffiti art seemed to also provide a sense that this loss or even abandonment itself was contextual and relative. People clearly hadn’t stopped visiting these rooms, and in fact might be visiting them more than when they were operational and cold.

Pictured: Photograph from interior of cold storage facility in Kentucky, 2016.

Photograph by Zak Argabrite

Their shifting importance means that abandoned spaces are ones that are in flux. They are not just transforming but transforming in remarkably uncertain or unpredictable ways. With abandonment, the loss of a space’s initial importance or designated purpose leads to a vacuum. In this vacuum, what to do with the space becomes unclear. The vacuum of importance can sometimes attract opportunities to reclaim a sense of importance—as illustrated by graffiti art. In many other cases, how long the uncertainty will last itself becomes unclear. This duration being subject to change is a transformation of abandoned space in a temporal sense. It can contribute to both the physical transformations of these spaces referred to earlier and the perceptual transformations in what is regarded as important about the space.

Whether through graffiti, or custodial neglect, people use their own agency to interact (or not) with a space. The complex interplay between the agency of people and spaces is entangled with the transformations discussed thus far that spaces undergo when they are abandoned: transformations in their physical form or appearance, in what is important about it, and in its status (or stasis) through time. These agency-fueled transformations also constitute a broader transformation in how that space is imagined or understood as a place. They shift who holds a stake in the place, who can access or hold a relationship to it, complicate the identity of space, and alter how it is perceived.

Sound of Abandoned Space

On the topic of perception, perhaps some of the most interesting transformations related to abandoned spaces are the ones that can also relate to sound. What are the sonic implications of an abandoned space? Abandonment changes a building’s structure, relationships, and timeline—in what ways does it change how it sounds? Do those sounds portray these spaces’ sense of place? How many of a space’s stories are told by their ambient sounds? These sorts of questions accompanied my encounters with abandoned spaces years after my first experiences with my Dad. In 2016, I began to make recordings of and in abandoned spaces. During this time, I visited a dozen or more sites including train tunnels, factories, and homes.

Pictured: Photograph from room of abandoned house in Kentucky, 2017.

Photograph by Zak Argabrite

My approach to this initial project involved using a computer to create a small archive of convolution reverbs based on impulse responses from several spaces. For the unfamiliar, convolution reverb is a technique used by sound designers to electronically create echo effects based on the unique ways that echoes are produced in a particular space. Convolution reverbs are created by recording an “impulse response”—a single, short sound of a certain loudness, then uploading the recording of that sound into software which is capable of making a simulation of the acoustics of that space. The effect has a few common applications, for example, it can later be applied to any recording—even ones not recorded in the original space—creating the illusion that the sound was recorded in the space. Properties of the effect can also be digitally transformed, such as changing the duration, or other aspects of how the space reverberates sound.

I did not initially create convolution reverbs of these spaces to use as an effect in computer-based creative projects. My goal in creating these was simply to preserve the unique acoustic fingerprint of potentially volatile spaces which may cease to exist, or where access may become impossible in time. It was also a first exercise in a longer project to gain a better understanding of sound in abandoned spaces. Conceptually, I wanted to create artefacts that would portray a sonic sense of the place—responding to the transformative, uncertain, and temporary nature of abandoned spaces. In my experience of listening back to them, I recognized a creative fork in the road. In one path of the fork, I could imagine a larger project (albeit with funding or access to better equipment) to preserve a series of abandoned spaces’ sonic sense of place. This hypothetical project could improve on my still-new process with technologies such as ambisonics—creating ambisonic convolution reverbs using ambisonic microphones.

As it happened, the experience of recording for these efforts revealed another path, one conscious of how I existed in that space, through certain questions. Many of these questions were familiar to me from past experiences making field recordings in other places. As an animate being, I am constantly making sound. How does my presence influence the composite of all the sounds of the space? In what ways does it interfere, obscure, or cover? In what ways does it resonate? What meanings could those sonic relationships and interactions have, beyond sound? How many of my footprints does it take until the space is no longer the same? What consequences does my being here have? What perspective am I listening to the space from?

In noticing my involuntary sonic contributions, my mind begins to move from preservation to performance. What types of sounds are suggested by the sense of place I experience from an abandoned space? Can certain sounds present in the space be mimicked, or reinforced? Do certain sounds resonate differently in this space than they do in venues designed for music? How does making sound in such a space help tell its story? How does the way sound is performed in a space respond to its sense of place? Conversely, how does performance in a space change that space’s story? How does performance change a place?

This line of questioning led to creative approaches that focused not on preservation, but real-time performance. In this performance, I am the performer, but also the listener. To me, this double role meant my performance was sparse, careful to perform as one of many sources of sound in the space. It meant acknowledging the many sounds that would play continuously with or without me. There was music going on that I had to be careful not to cover up too much. The sounds of the place itself were the special guests on this recording, and I was conscious to not assume I was invited or necessary as a performer or a listener. I was acknowledging and understanding that space’s agency, and that meant understanding my performance as a collaboration with a space-as-performer.

Amid these initial experiments with performance, I began to wonder about the implications of inviting collaborators to join me. Specifically, I again wondered, how many footprints does it take until the space is no longer the same? What is revealed from another perspective? What types of sounds might another person make in response to the place? How does the context of the specific place, and all the sounds that come with it, affect how we perform together? This curiosity resulted in two projects which inspired many of these questions and informed our performances.

For the first project, my collaborator J Clancy and I recorded in a network of train tunnels in Western Manhattan. Trains still travelled through one main branch of the tunnel, however with less frequency than they once did, and with many unused rooms and passageways branching off from it. The tunnel was wide enough that it was easy to stay out of the way of trains, and trains were loud and bright enough to be noticed with plenty of time to avoid danger. Throughout the tunnels, there was metal infrastructure and loose materials. The ground comprised gravel, and the tunnel itself concrete and metal. There were air shafts in the ceiling with grates in a sidewalk above it.

Pictured: Photograph from partially-abandoned train tunnel in Manhattan, 2018.

Photograph by Zak Argabrite

Ambient sounds of the space changed as we walked through the tunnel. Near where we had entered, outside sounds coming in from the mouth of the tunnel and air shafts in the ceiling blended with the sounds of the tunnel itself. Further in, air shafts became less frequent or were covered up, the mouth of the tunnel became barely visible, and sounds of the outside world began to disappear—the tunnel’s ambient sounds became more independently apparent.

Pictured: Photograph from partially-abandoned train tunnel in Manhattan, 2018.

Photograph by Zak Argabrite

Different locations within the tunnel provided different materials for making sound as well. Near the entrance, rusted metal pipes and beams were scattered on top of the gravel where matching rusted metal meters sprung out. Even further in, a staircase that made low booming sounds as you walked up it wrapped around a rattling metal cage with a broken bicycle inside it. At the top of the staircase was a room where dirt floors and shafts of outside light and wind had grown a thick patch of rustling wild grasses.

As a percussionist, J was interested in the unique sounds that could be produced with the metal pipes. These would ring out because of their hollowness but also activated the resonance of the space itself. They were also covered with rust, which would peel off if scraped. The scraping was audible and softly resonated the pipe, which we recorded by placing microphones close to the pipe. Through this collaborative improvisation with the metal materials, I returned to the question: how many footprints does it take until the space is no longer the same? In this context however, the question seemed to be, how many of our fingerprints would change these materials? On the one hand, there was a sense that this way of performing was activating inactive (perhaps themselves abandoned) resonances in these abandoned materials—an observation which I would reflect on more later. Yet, on the other hand, this way of performing was informed by an intent to do so non-destructively, appealing to an ethics of existing in the space respectfully. Striking this balance was also on my mind during other performances we made in the space.

Pictured: Photograph from partially-abandoned train tunnel in Manhattan, 2018.

Photograph by Zak Argabrite

Through my initial experience of performing with someone else in this abandoned space, I noticed that, in addition to gravitating towards percussive performance possibilities that I wouldn’t have necessarily tried on my own, J was less hesitant than me to make sound in the space. My earlier, more hands-off approach continued in this first collaboration, and I made less sound than I would in another improvisational setting with J. However, I was also more inspired to, at times, attempt a more active approach to making sound in the space than I would have in earlier solo performances.

Pictured: Photograph from partially-abandoned train tunnel in Manhattan, 2018.

Photograph by Zak Argabrite

Excerpt of concrete ambience II (2018), by J Clancy and Zak Argabrite. Recorded in a partially-abandoned train tunnel in Manhattan.

Another development from this collaboration was that J had brought an instrument—a melodica—to play in the space. This built off considerations of performance initiated by playing with the discarded metal materials. J’s approach to performance with the melodica involved a strategy which interested me in this regard: mimicking sounds that already exist in the space, but using non-endemic instruments to do so. This seemed to re-enforce specific resonances or multiply repeating sounds, which drew more of my attention to subtle sonic details present in the background. This felt like an extension of what I had noticed from performing with the abandoned metal materials in the space. There was a sense that this activated certain unnoticed, less active, inactive, or perhaps even abandoned sounds. So, while I was likening performing with abandoned materials in the space as activating abandoned resonances in these materials, performance here seemed to also activate abandoned resonances within the space overall. These observations have fueled some of my most important reflections on how abandoned spaces can inform understandings of wider topics of performance, instruments, and space, which I will turn to in the next section. These observations were further developed through another collaborative project: with drummer and sound artist Mark Ballyk.

Pictured: Photograph of recording setup from within a metal pipe in an abandoned train tunnel in the Bronx, 2018.

Photograph by Zak Argabrite

For this project, Mark and I located a train tunnel in the Bronx by following several different abandoned elevated rail lines. This tunnel was much shorter, narrower, and remarkably more resonant than the one I had recorded with J. Unlike that previous project, this tunnel existed further along an abandonment timeline: it no longer had trains actively passing through it, and had water which had pooled up in the middle, near where the tracks lay—leaving just enough room to walk along the edges without having to wade through the water. There were indents in the walls of the tunnel, like small cubbies, perhaps to provide a safe space for people to stand while trains passed through.

Excerpt of stone ambience I (2018) by Mark Ballyk and Zak Argabrite. Recorded in an abandoned train tunnel in the Bronx.

The cubbies provided an interesting space acoustically. Their nearness to being a separate room was interesting, particularly because of the contrast in size between the tunnel and the cubbies themselves. Their connectedness to the tunnel space also meant that sound made inside them projected into the main tunnel. And yet, I perceived the cubby as having some acoustic separation from the main space. This distorted the ability to locate the sound within the space, and in listening to the recording, to me, this quality seems even more exaggerated without visual information.

Excerpt of metal ambience I (2018) by Mark Ballyk and Zak Argabrite. Recorded within a large pipe in an abandoned train tunnel in the Bronx.

Pictured: Photograph from within an abandoned train tunnel in the Bronx, 2018.

Photograph by Zak Argabrite

Our improvised sonic exploration of this space led us to reflect together afterwards on the experience. For Mark, the experience had suggested a metaphor of shining a flashlight in a dark room—where our performance was the flashlight, and the light itself was representative of the resonances activated from this performance. For me, this metaphor provided an interesting analogy to the concept of activating abandoned resonances in these spaces which I had first noticed with J. Mark had several additional reflections on how the experience of being in these spaces transformed his perception of place. He remarked that these spaces were interesting in a city as dense as New York, that they felt like holes themselves—by comparing them to a large-scale game of Tetris, where the urban filling-in of land with a built environment had resulted in these small voids of space and real estate importance. Through this observation, we both acknowledged this influenced how we experienced place while in these spaces. Specifically, we felt we were on the outside of urban space, exempt from its crowdedness in a distinctly empty place, peering inside the centre of a city from a curious perspective. Simultaneously, we felt inside of a void—a hole in the urban construct—watching and listening to the outside world from within.

Excerpt of stone ambience II (2018) by Mark Ballyk and Zak Argabrite. Recorded in an abandoned train tunnel in the Bronx.

Just beyond an abandoned space

Mark’s and my conversation around the territoriality of abandoned space and its confusing, transformative boundaries has replayed in my mind as I have since reflected on these types of spaces and what meaning my experiences in them might have on my day-to-day creative practices. A lot of my daily creative focus is on instruments and other materials for sound-making. With these materials, I am specifically interested in the nature of their relationships with the artist who performs with them. Through my experiences with abandoned spaces, I developed a curiosity about how thinking about sound in these spaces might inform how a person generally performs sound—with instruments and other materials.

This question of whether there is a deeper relationship between abandoned spaces and instruments has also come out of a question about the scale of spaces: how small of a space still counts as a space? Most of the examples of spaces mentioned here have been at least big enough for a person to squeeze inside, but are the resonant bodies of instruments (for example) not in some way a space? While some people might find this a stretch, with a little imagination, I have found this to be an interesting question to say yes to. In fact, I would like to extend an invitation to the non-initiated to imagine shrinking down to a miniature size for an expedition into the guts of a piano, the body of a guitar, the barrel of a clarinet. For the more electronically minded, maybe it’s off to find out what it’s like among the circuit boards inside your computer or synthesizer. For singers or wind instrument players, maybe it’s even off to your own lungs, or for that matter anywhere in the body, perhaps the muscles of your own hands. Either way, imagine these spaces as a much smaller relative of the concert venue.

While inhabiting these miniature spaces, let’s return now to the idea of an abandoned space: Can we talk about instruments or other materials involved in a sound-based performance having abandoned spaces? Perhaps certain “extended” techniques of playing an instrument come to mind—techniques that produce sound on parts of an instrument that would not typically be involved in performance. In this case, the technique or method of performance is a form of exploration of an abandoned, unused, or at least less-travelled miniature space.

Around the same time that I collaborated with Mark and J, I worked on another project which explicitly attempted to explore these types of instrumental abandoned spaces. The project was a musically notated piece with flautist Leia Slosberg. For the project, I studied a particular abandoned factory while also considering what “miniature” abandoned spaces might exist within Leia’s instrument. I attempted to “map” these spaces notationally, both for the flute and the factory, to attempt to provide some insights into my questions around how these all might relate. I notated the piece in such a way that there were choices in how sounds or progressions of sounds would be ordered. The idea was to create a map of different sounds that Leia as the performer could explore, in a similar manner as one would a building or other space, in an effort to connect this back to the exploration of abandoned spaces.

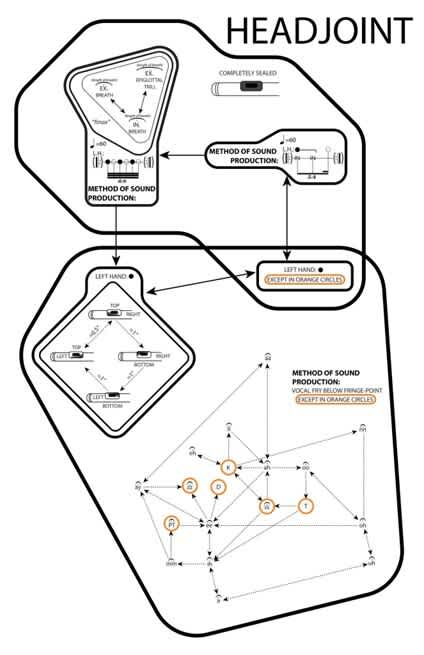

Pictured: An excerpt from the score for open/closed (2017) for flute and amplified table, by Zak Argabrite, written for Leia Slosberg. The excerpt focuses on actions performed with just the headjoint of the flute, and shows the diagrammatic and instructional nature of the notation. Diagrammatic zones notated by rounded thick black borders detail different actions. Zones within zones refer to actions happening simultaneously, while discrete zones can be alternated between, following arrows.

In my exploration of the abandoned factory, I transcribed words from graffiti there that I found relevant to some of my overall questions about abandoned spaces and their relations. These words were incorporated into the composition as shown with the letters at the bottom of the excerpt shown above. The particular vowel and consonant sounds that make up each word are notated as individual sounds. The sequence of these sounds to form their respective words are noted with arrows. Vowel and consonant sounds that appear in more than one word are not reproduced more than once in the notation. The result is that, for many sounds, multiple possible sounds can proceed after, similar to the other sounds notated in the piece. The words from the graffiti in the actual abandoned factory form a conceptual or notational architecture which is explored through performance. The way these vowel and consonant sounds are produced are further complicated by the fact that the performer performs the sounds using a vocal fry into the flute. The abandoned factory therefore inspired a way of exploring an instrument, and exploring the unexplored, unused, or even abandoned sounds of that instrument.

Similar goals around finding abandoned sounds or resonances in instruments, or the relationship between abandoned spaces and performance in general, have also influenced my own emerging approaches to performance on my own instruments. For example, in recent years, I have taken a similar approach to my clarinet. This has included exploring sounds in a similar manner as in the flute project, and it has included exploring preparing my clarinet with non-clarinet abandoned materials, such as discarded corrugated plastic pipe fixed into the chain of pieces that are traditionally assembled to make up the clarinet.

The incorporation of abandoned materials, and an exploration of their own abandoned sounds has been the focus of another side of my performance practice—circuit-bending. This practice involves opening discarded electronic materials to explore their potential for sound-making. Specifically, this technique involves bridging previously unconnected points on the circuit boards of these discarded devices with pieces of metal, such as scrap copper wire, until unexpected sounds are produced from the device. Over years, I have developed and continue to develop new methods of this type of performance. To me, these experimental performance practices inspired by abandoned spaces demonstrate a transformation of material and performance which is related to the transformational qualities of abandoned spaces. These qualities, in the context of performance and instruments, are something which I feel has a great amount of potential: to further these unique understandings of performance, instruments, and abandoned spaces themselves.

Conclusion

Throughout these projects, I have been particularly struck by the multiple ways that these abandoned spaces transform in interrelated ways: physically, in what is regarded important about them; their timelines, in the sense that the space evokes a distinct place; and in the sounds present in the space. The shift in how the space is regarded as important can determine how long it sits abandoned, or whether the space remains intact. For the ones that do not—the formerly enclosed spaces—perceptions of them as a place, and the physical properties of the space, change, and this also impacts sound in the space. Changing ambient sounds in a space can further transform how it is perceived as a place.

While discovering these related transformations in abandoned spaces, I observed the uncertainty, fragility, impermanence, and solitude of these spaces, and how these qualities emphasized the impacts of my presence in the space. My experiences with collaborative performance and improvisation in abandoned spaces taught further lessons in the overall possibilities of sound that exist within a given space. Such possibilities include sounds of endemic materials, idiosyncratic acoustics, and the ability to project and reinforce the unique ambient sounds of the space.

Reflecting on my cumulative experiences in and observations of abandoned spaces has in turn led to some unique considerations which present further opportunities related to instruments, materials, and performance. While I have begun to explore the ideas presented through my projects and writing, there is still so much potential for more: more ways of understanding abandoned spaces, their relationships with sound, people, and beyond; and, more ways of understanding these spaces’ importance, value, and transformation.

Zak Argabrite is a multi-disciplinary artist and researcher from Kentucky based in Te-Whanganui-a-Tara by way of Lenapehoking (NYC). Zak's practice spans woodwind explorations, circuit-bending, improvisation, notated composition, and live audiovisual performance. Conceptually, Zak’s creative work has focused on kinship relationships the materials he works with has with people and land.