Questions for

Phil Dadson

Tell us about yourself right at this moment: geographically, musically, artistically, personally…

Maintaining body-rhythm coordination, mental agility, emotional stability is an ongoing balancing act. Managing personal energy and being effectual with a practice, family, household, whatever, means putting in the graft mentally, emotionally, physically so I don't wobble too far off the pivot. So when you ask where am I and what am I doing right now art/music wise, on one hand there are fractures and slippages in the transmission, and on the other, a sparkle of brain cells firing and stored body-memory kicked back into action. Not so much from personal art practice but more so from a fast-tracked revival of essential skills necessary for a well-honed From Scratch participant. And right now I'm ranking about 7 out of 10 if that! You might say struggling a bit to keep up with the challenging mix of meeting those first three requirements. From Scratch, through the month of September this year, celebrated what we calculated to be 625 moon cycles from the first public performance of the group in 1974, through to this September 2024, i.e., fifty years plus some six or so months.

Pictured: 625 Moons poster. Through September this year, 2024, Audio Foundation in Tāmaki Makaurau hosted a one-month residency with From Scratch to celebrate 625 moons (50 plus years) of music-making. Eight separate events took place through the month; an exhibition of instruments, photographs etc; a rhythm workshop; and six collaborative performance nights with invited composers, musicians, and moving image makers.

Poster by Richard Francis

My interest in this is not so much with the past or the future but with the present, and being challenged by the enthusiasm and energy of my excellent partners in the collective. Frankly, I thought I'd put much of this behind me with the decision earlier this century to put two things in the back drawer—teaching and From Scratch—and focus on my art practice, but From Scratch continued to hover in the background like a cool T-shirt that keeps shuffling to the front. Why continue? As much for the bonded fraternity of a group of guys—Adrian Croucher, Shane Currey, Darryn Harkness, and Chris O’Connor—whose talent, loyalty, and enthusiasm has nurtured the performing potential of FS, as for the basic egalitarian collective philosophy, the instrument invention, and rhythmic language intrigue, which, together, continues to speak volumes to me in times of planetary fracture and unrest.

Promo video clip for the 555 Moons From Scratch exhibition and performance series at Wellington City Gallery in 2019. This followed on the tail of the 546 Moons event at Te Uru Contemporary Gallery in West Auckland in 2018 where the group exhibited and performed with additional members and collaborators at the invitation of Auckland Arts Festival. A national tour of the core group followed in 2020.

How did you come to music/sound/art/making?

The Marewa (Napier) Primary School mouth organ band was my first experience of collective music-making—unforgettable, as much for the dictate that prevented us foot-tapping demonstrably (toe motion within our shoes was allowed, providing no one noticed). Probably every musical adventure I've had since then has been to obliterate that very restriction. Anyway, when about 12, I requested a piano and the good parents purchased one, on which I learnt to play a mediocre form of light classical, then boogie woogie, and later jazz piano and improv’ inspired by the greats. My older brother Kerry left a Hank Jones LP with a record player in the room I inherited when he left home to go to sea as an engineer. I then joined up with World Record Club and bought my first two records: Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring and Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue. Parallel with this, my best marks at school were for art and so the two evolved in tandem with me eventually going to art school, playing in the Akl Uni’ jazz quartet, experimenting with tape recorders at art school, and so on, until I took a break from Elam to go to London, looking for ways to combine my interests in art and music, and my life changed. I discovered the Morley College experimental music class run by Cornelius Cardew and others—a class that became the foundation group for scratch orchestra and things took off for me from there. Scratch Orchestra NZ came into being while I was a student in sculpture, later followed by the formation of From Scratch, whilst struggling to work as a filmmaker and sound recordist… and so on.

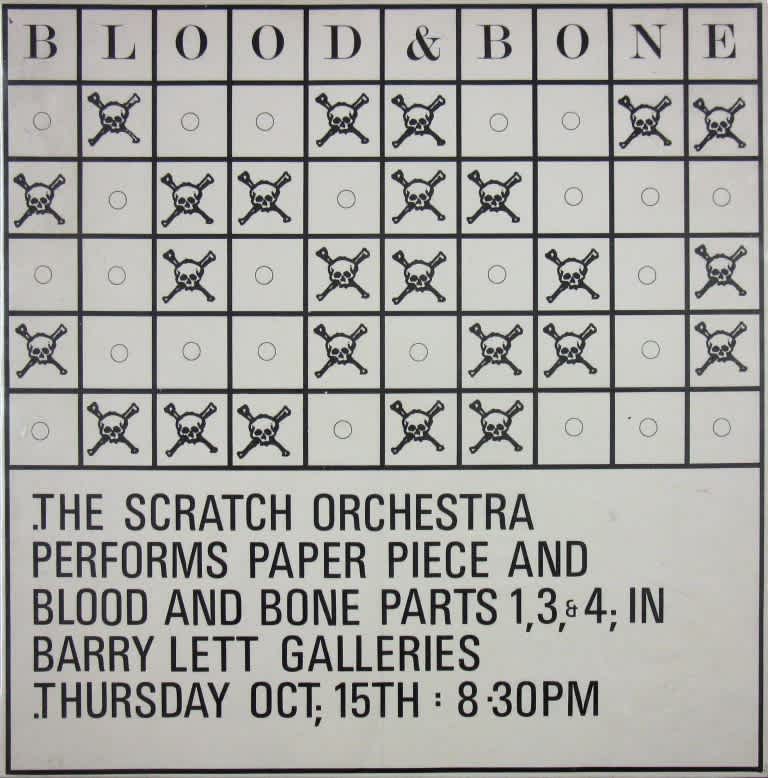

Pictured: 1970 poster for a scratch orchestra event at Barry Lett Galleries, Auckland. Blood & Bone is an early composition of mine, a simple 5x10 grid device for structuring chance-oriented, timed action/rest periods.

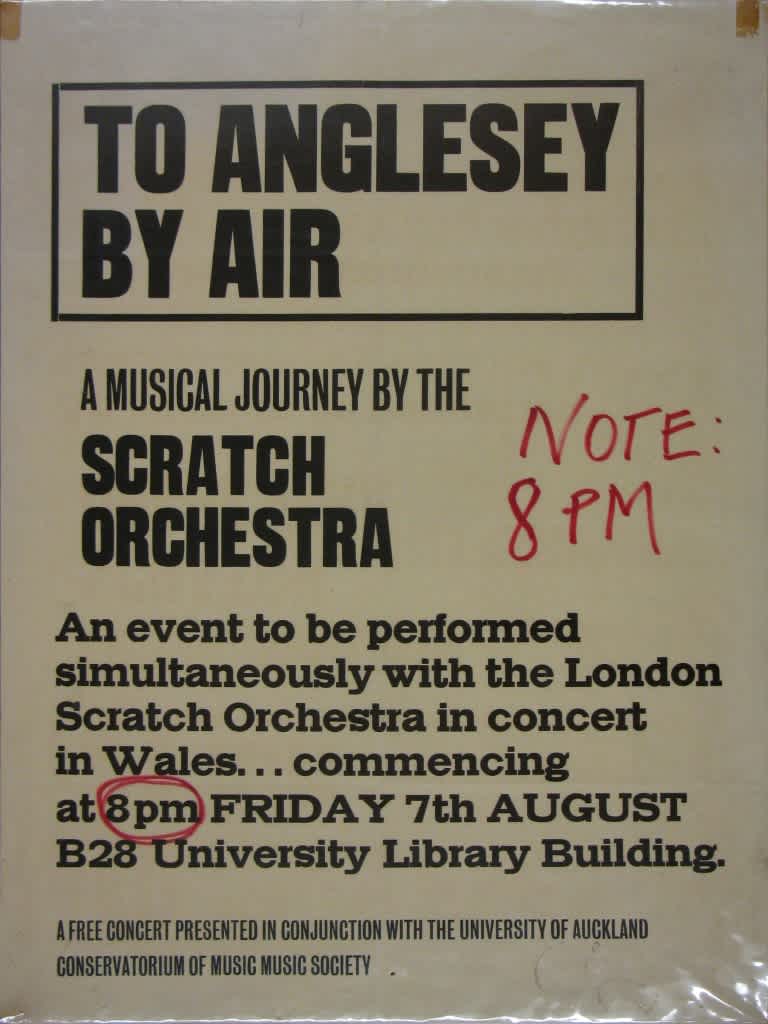

Pictured: 1970 poster To Anglesey North Wales by Air, a long-distance simultaneous music event between two scratch orchestras, NZ and UK. Facilitated via the mails, Blood & Bone was used to synchronise event durations between the two orchestras, a flag up for one performing while the other listened and vice versa. Spanning space by ear and imagination.

Can you tell us more about how you see the two artforms (visual art and music) developing in tandem in your practice, and how this has continued to evolve over the years since?

Initially, the development of my visual art and music interests were separate until I broke my Elam course to spend time in London during 1968—a life-altering experience. I was lucky initially to score a part-time job as a printing assistant at Editions Alecto, working on projects by Oldenburg, Hockney, and others. Looking further afield for ways to unify my interests, I discovered the experimental music class at Morley College for Working Men and Women and enrolled. It was run by a triad of composer-performers—Cornelius Cardew, Michael Parsons, and Howard Skempton—none of whom I knew of at the time. There were others also but it was Cardew who, as an artist/composer himself, essentially drove things along a Fluxus-cum-cross-media approach to composing, improvising, and performance. This, and the post-object performance art and conceptual scene of the time, were significant influences on how things developed for me from there.

What was it about the Morley College experimental music class that spoke to you? How was that space created to spark your creativity, joy, and collaborative spirit?

The class was a liberating, playful, and inspirational once-weekly Friday night, followed by a visit to a local pub. It attracted a lively mix of composer/musicians, visual artists, and a few from theatre, and soon became a guiding influence and direction. During that year of the class, Cardew introduced his scratch orchestra constitution, a proposal that rapidly transformed the class into the foundation group for scratch orchestra. All in the class contributed ideas, compositions, and improvisational triggers, later to become Nature Study Notes, a collection of improvisation rites, along with a series of anthologies for composition, task-oriented performance, etc. Returning back home to NZ in late ’69, and then back to art school and into sculpture at the invitation of Jim Allen, forming a local scratch orchestra was the first thing on my mind. And so it evolved, initially in regular communication with Cardew, later more so with Michael Parsons, who I'd developed a close friendship with.

How did From Scratch come about, and what was/is the ethos of the group?

On returning to Elam I was lucky, firstly, to have the support of Jim Allen and Greer Twiss to establish an offshoot of the UK scratch orchestra back here in NZ, within the hot-house of Sculpture. Jim was instrumental in expanding the boundaries of Sculpture at the time, and along with Greer Twiss gave me full freedom to explore music-art concepts and get the scratch collective up and running. This gave me freedom also for a more conceptual approach to visual space, form, and content, along with a realigned approach to experimenting, with the fundamentals of visual art and music, with time, duration, structure, and improv’ as the common glue. This, in turn, led me naturally into filmmaking and subsequently video art (early 70s) and an intermedia practice that has continued through to the present, where the synergy of sound and image combine in various ways. It would be generally true to say that my essentially visual work foregrounds sound in one way or another (the various visual-music projects through the years), and that the essentially sonic output is similarly layered with visual concepts of 3D space, motion, colour, and form.

Between Worlds, 2011. A world-upside-down (WUD) view intersecting with reflections on ecology, geometry, nature, signs, and portents. This work explores the interstice between inner and outer worlds, tangible and illusory spaces. Commissioned by circuit.org, Between Worlds is a sequel to the Deep Water trilogy.

The formation of From Scratch came about as an offshoot of Scratch Orchestra, a breakaway, rhythm-oriented hub to initially explore process and polyrhythmic ideas. The ethos was and continues to be egalitarian, experimental/exploratory, socialistic, and collaborative—features inherited pretty much from Cardew and Scratch Orchestra, and added to with the philosophical and left wing convictions of the original From Scratch foursome—Geoff Chapple, Bruce Barber, Gray Nicol, and myself. Co-operation and a collective spirit has been a consistent feature through the years, qualities that have pervaded the membership and the various compositions and performances through the years.

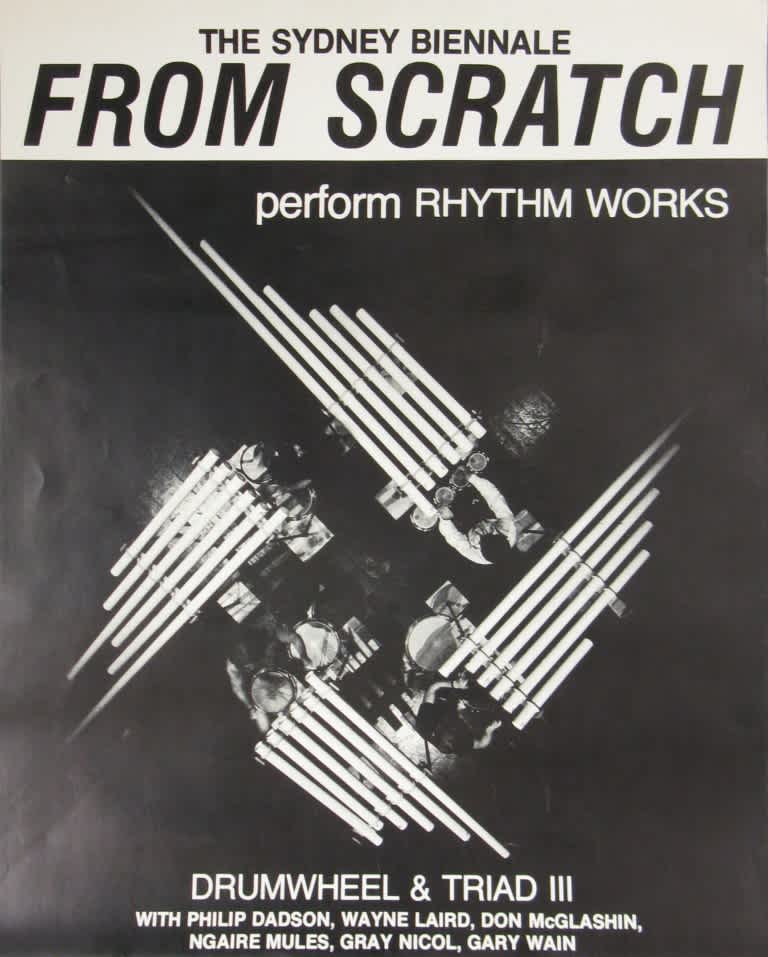

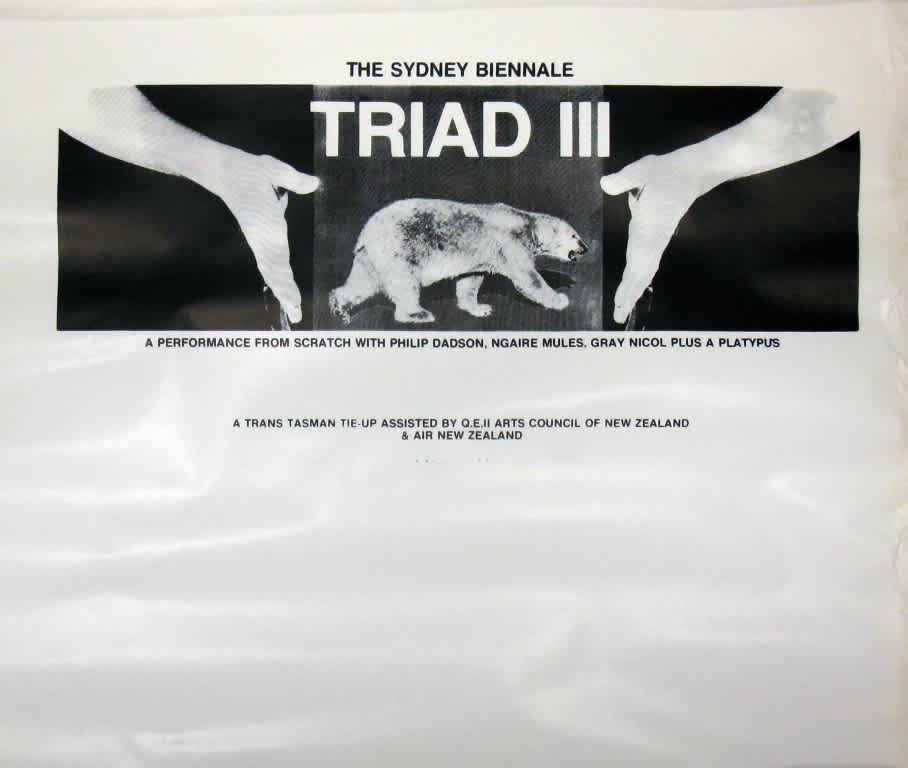

Pictured: From Scratch posters, 1979. For presentations at Sydney Biennale for performances of DrumWheel, Out/In and Triad III. Triad III was a separate mixed media performance piece for live actions referencing pairs of opposites, triggered by film and slides, performed by Gray Nicol and Ngaire Mules.

This issue of BLOT has a focus on space/s. Your work exists happily in visual art and experimental music contexts and across multiple types of venue and media spaces. Could you comment on these aspects?

A good question that prompts me to contemplate mind space, outer space, inner space, conceptual, and real—the ways we individually perceive and understand space as physical, durational, imaginatively, and instinctively. I am fortunate to live in close proximity to an estuary where the tide ebbs out and flows in within a constantly modulating ambience of light and shadow, motion and stillness. While I think the ways in which space manifests in my mixed media expressions are largely intuitive, the experiences of physical landscape, the breath, and modulating rhythms of light and nature’s influence, from childhood to the present day, all, no doubt, play large in terms of dynamics, duration, structure, and atmosphere.

An aeolian (wind) harp I devised for Koea o Tāwhirimātea—Weather Choir, 2023. A collective project curated for Huarere—Weather Ear, Weather Eye exhibition, hosted by Te Tuhi Contemporary Gallery as part of the World Weather Project. This clip was made more recently to support the Palestinian cause and a two state solution to the conflict.

What gives you hope?

I’m intrigued you ask me about hope. In some ways, I wonder why this question, but then, why not? Hope is on the flip-side of decay and destruction. Hope is an expression of sunlight, growth, flowering, and regeneration. Without hope we would buckle and be trodden under by dense and dark forces. Hope, as I recall, is a seminal character in the drama of being human. My hopes are twofold: externally, for the evolution of the intelligence of our species; and internally, for the conquest of a few lingering demons and the growth of my spirit.

Phil Dadson has a transdisciplinary practice including invented musical instruments, composition, improvisation, digital video, sculpture, graphics, and notations. Since the early 70s, his practice has foregrounded sound and referenced body, land, triadics, nature, and the human condition. Dadson founded From Scratch and is represented by Trish Clark Gallery and circuit.org.