Cleaning the Old Folks Ass

Stephen Bain

Let’s clear the elephant out of the room: cleaning an old folk’s ass, whether it’s one of your own old folks or someone else’s, is not a pretty task. The day you find yourself in this situation, you’ll understand what I mean. You make up the rules as you go, you do the best you can, and you wonder, “who will do this for me when that day arrives?” We all came into the world requiring help and we’ll leave this world in much the same way.

Cleaning the Auckland Old Folks Association Coronation Hall, on Gundry Street in Tāmaki Makaurau, is a more palatable affair. On one side of the building, the name is abbreviated to “Old Folks Ass” and the symbolic parallels are not lost on sniggering passers-by, who discover the faux pas as they meander off Karangahape Road and find the building down an industrial side street opposite a high-art auction house.

The challenges to cleaning this iconic, independently-operated community hall sometimes stretch to picking out vomit from the hand basins, removing vile-smelling experiments from the courtyard, and hosing down body fluids left in the entrance alcove on a Sunday morning. But there are times when the Old Folks Ass saved my ass too. It gave me a place to be. It welcomed me at times when institutional performance spaces were all tied up in self-promotion.

Pictured (L-R): Old Folks Association Hall on Gundry Street, 2024; Teapots for every occasion, Kitchen, 2024.

Photographs by Stephen Bain

I was introduced to the hall in the early 2010s by mutual friends in the experimental performance scene. Over time I was invited to become a committee member (there are currently seven of us), then around four years ago I put my hand up to look after the day-to-day duties of booking the space, introducing newcomers and making sure the space was cleaned. It was at this stage that my thinking shifted about how a community hall works, who it’s for, and what’s the point. I imagine it’s a bit like looking after a mountain: you find your place in the relationship and don’t expect anything particular in return.

Full confession—I’ve always harboured a secret admiration for Dwayne Schneider, the character played by Pat Harrington Junior in the long-running (and in retrospect painfully moralistic) American TV sitcom One Day At A Time (1975–1984). Schneider was a moustachioed, key-jangling janitor who turned up daily at the Romano household, comprising a divorced Mum and two teenage daughters, living in a downtown apartment in Indianapolis. He’d drop in uninvited on the premise of fixing things but we (the viewers) could see it was he who was getting looked after, as his and the Romanos’ lives became intertwined.

As the self-appointed janitor of the Old Folks Ass, I pinned a coat hook to the back of the door in the storeroom and hung my overalls on it. I was in there almost every day during the lockdowns fixing a door hinge, painting a wall, filling a crack in the floor. Just like Schneider, I dropped in because it was me who needed looking after, because being a guardian is for your own good.

An idea turns into a building

For those who haven’t studied the portraits and framed letters hanging on its interior walls, here’s a brief history of the Old Folks Association. The group was incorporated in 1945, creating a space for senior citizens (then defined as those over 60 years old) to meet for social gatherings. Their clubrooms were located in the Legion of Frontiersmen Hall, then moved to the Church of the Epiphany Hall on the corner of Karangahape Road and Gundry Street (now demolished).

Pictured (L-R): Entrance to the Old Folks Hall on Abbey Street; Ceremonial silver trowel with the inscription “this trowel was used on June 28th 1952 by Sir William Jordan to lay the foundation stone of the Auckland Old Folks Assn. Coronation Hall,” and brass plaque with a framed photo of a celebrated committee member, which says “tribute to Mrs E. Bryant,” 2024.

Photographs by Stephen Bain

In 1952 after some serious fundraising efforts, and aided by coronation grants from the New Zealand Government between King George VI’s passing and Queen Elizabeth’s coronation a year later, the association was able to build a community hall “to provide Club Rooms where members, irrespective of status or creed, may meet for social reunion and entertainment and games and the like. To provide games, library and furniture and other facilities for the entertainment and recreation of members”.1

Fletcher Construction Company completed the building in 1953. There was a steady membership of around 400 over the following two decades, holding regular events such as dances, games, socials and group outings.

As the Northern and Northwestern motorways in Newton gully expanded throughout the 1960s, the aged population in the area decreased dramatically. Thousands of homes were demolished for the spaghetti junction on- and off-ramps now separating Newton from the ridge on Karangahape Road.

By the 1990s, membership of the Old Folks Association was low and upkeep of the building waned. The hall was still regularly used by cultural groups and local residents but the building was not well maintained. By the early 2000s, an elderly group of volunteers welcomed the help of artist Sean Curham. He had become a regular user of the hall for his own choreographic practice, and assisted with maintenance and compliance issues.

In 2006, Sean was co-opted on to the committee and by 2011 the committee had resolved to remove age restrictions for members, to add the words “arts and culture” to the resolution, and ensure that the association’s heritage and availability to the community would be secured.

Unlike many spaces that depend on institutional support, today the Old Folks Ass is still an independent hall for hire. The committee has a clear arts and culture agenda, and committee members are now predominantly aged under 60. In the wake of a local real-estate boom and subsequent growth of inner-city apartments, it has become an unofficial home to experimental performing arts.

Part of my slow discovery of the hall included uncovering the archives, a jumbled pile of hand-written books from 1945 to the 2000s, containing the minutes from every meeting the Old Folks Association had. I use the word “discovery” deliberately because that’s how you feel when you stumble on objects that have a history unknown to you. It’s a seductive sensation that we learn as children, an ego-centred fantasy that things of great worth are just waiting for our acknowledgement to become re-actualized.

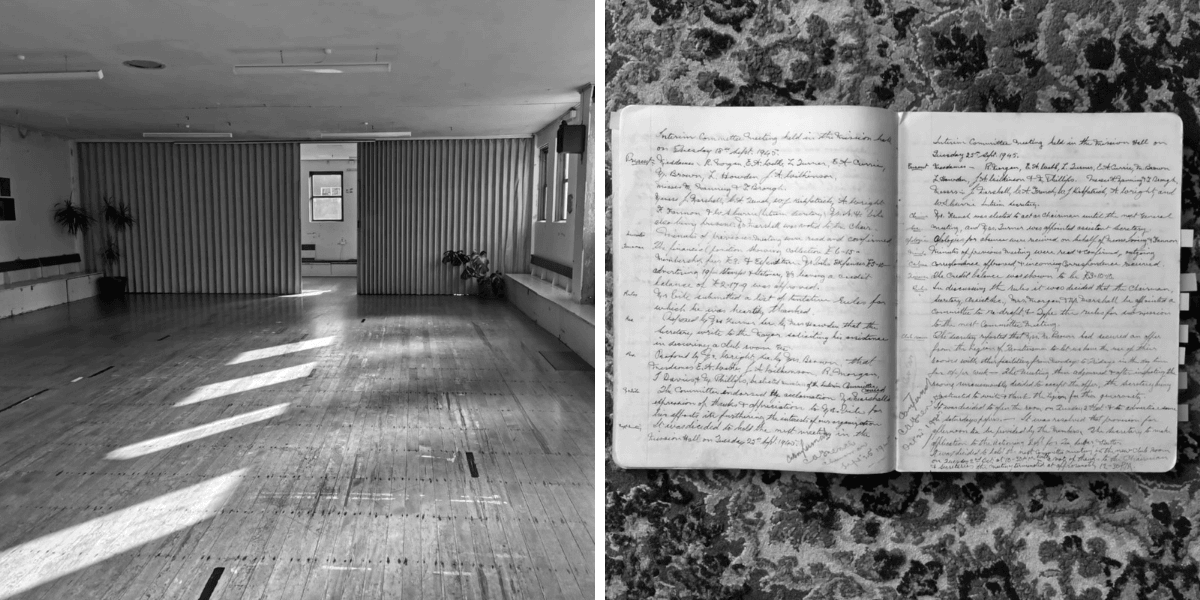

Pictured (L-R): Interior of the hall facing South; Handwritten minutes from 1945.

Photographs by Stephen Bain

The beautiful blue-ink hand-written script of the minutes from the mid 1940s flows like ring bark on an old tree, each nuanced layer an insight into a season’s growth. The formal language is something else, not just in the perfectly formed handwriting, but in the way each member is addressed: “Mr Johnston proposed that Jasper Calder be thanked for the very lovely launch trip which was enjoyed by all” (OFA Minutes, 15 Feb 1949). Each committee meeting is formally recorded, noting who says what and how much is spent, creating a deliberate snail trail of democratic adherence.

By the early 1960s, a typewriter must have been purchased, and the minutes get decidedly easier to read. I graze through large swathes of minutes from 1960 to 1974, through which a sense emerges of the community the Old Folks is creating. Relationships flare up, power plays emerge, committee members walk out in a huff.

Increasingly elaborate rules are established, determining who is allowed in and who is kept out. Paid membership begins as a transparent process of nomination and becomes incrementally conditional. Veto powers are held by the Secretary (Oct 1966). Two prospective members who are not yet 60 but have physical disabilities are rejected in 1962, the president citing “no reason any person should have preference.” Others are rejected from committee nomination because of a strict quota for the number of men and women at any one time, and after several incidents the Hungarian Society is pushed out for using the tea urns in a manner that is deemed unacceptable (boiling sausages).

The society’s rule to include members “irrespective of status or creed [religious denomination]” reflects the concerns of the time, implicating status and creed as biases that are very much alive and well.

Similar insights can be found in the 2011 amendment for the “furthering of arts and culture” and to protect the hall “in a way that ensures its heritage is secure and it remains available to the community at large.” These words imply the concerns of 21st century communities, protecting diminishing space for the arts, with the insistence that they must be protected from private interests. How many community halls in Central Auckland have fallen victim to the privatization of shared space in recent years? The Irish Society Hall springs to mind, just a few hundred metres up the road, demolished to create more room for a car yard in 2009.

The Old Folks book-keeping also records operating expenses for the association: 12 pounds 1 shilling 4 pence spent at Henshaws cakes in May 1961, inflated to 32 pounds spent at Eccles Cake Shop in November 1963. It’s not just an account of what things cost. It indicates how the Old Folks spent time together and how collective wellbeing was maintained by eating and drinking together.

The caretaker was paid 117 pounds for the year in 1961, which translates to around $12,000 today, allowing for inflation. The upkeep and preservation of space is apparently more worthy than the role of Secretary/Treasurer (104 pounds), and Program Organiser (52 pounds) (OFA Minutes, Nov 14, 1961).

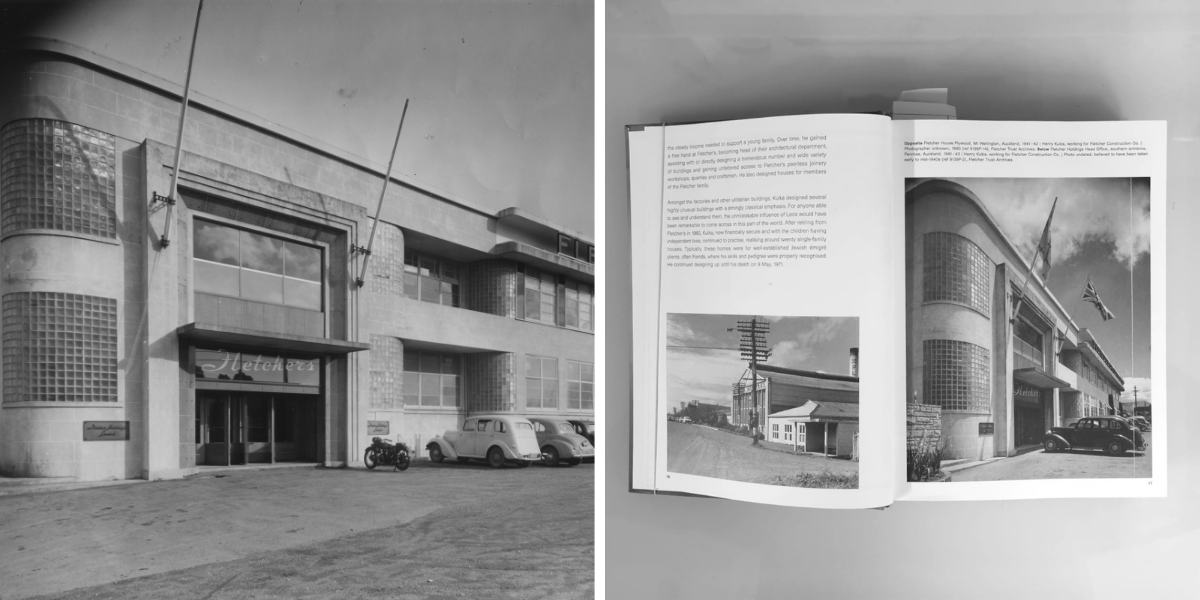

Pictured (L-R): Fletcher House, Penrose, 1941; a spread from the book Henry Kulka, featuring two Fletcher buildings.

Photographs by Fletcher Trust Archives, P9139/2 (L), Stephen Bain (R)

Academic research carried out by architecture students at The University of Auckland (see, for example, dissertations by Richard Goldie (1986) or Henry Ho (2010)) unveils the architectural legacy of architect Henry Kulka, leading to renewed interest in the hall. Kulka was a Jewish, Czech architect who emigrated to New Zealand in 1940. Until recently, Kulka has been a minor figure in NZ architectural history, despite his international recognition as assistant and colleague of Austria-based Adolf Loos, one of modernism’s champion architects. Kulka worked with Loos in Vienna, leading his practice after the celebrated architect’s death in 1933 until 1938, when Kulka and his wife were forced to flee the country due to Nazi occupation. Eventually accepted by NZ, Kulka was hired by Fletcher Construction Company as their lead architect and he went on to create an impressive body of work with the company until 1960, including many commercial buildings and private residences. He retired in 1960 and went on to design domestic buildings in Auckland until his death in 1971.

In 2022, English architectural historians Mary Gaudin and Giles Reid published Henry Kulka, the first ever book dedicated to the work of the architect in Europe and Aotearoa (available through Auckland Council Libraries), with mention of Auckland Old Folks Hall as “run down and disfigured,” yet assuring its place as a fine example of his pioneering modernism.2 Linking Kulka’s designs with the philosophy of Loos, the book articulates Kulka’s unique yet understated contribution to Aotearoa architecture.

“Henry Kulka’s designs have a quietness and intensity of feeling that are at odds with much of today’s media driven architecture, the need to land an image fast and move on. His plans do not reproduce as neat icons or summations of his thinking. His interiors create beautifully crafted but closed-off worlds, slightly distanced from their surroundings. There is a breadth and depth to the work, and a rigour of thought which remains true to itself, across a career spanning four decades and two hemispheres”.3

Lived Experience

Long-lasting architecture mixes functionalism with symbolic meaning, just as long-lasting politics and art are symbolically articulate. Ideas rendered into space outlive generations, shaping relationships and the materiality of our everyday lives. This is translated through the Old Folks Hall as the current home to a thriving independent art scene. Its unpretentious exterior opens up to an interior that is intimate and warm and constantly being “discovered” as if the discoverer is the first person bestowed with this forgotten gem. Located just off the urban grittiness of Karangahape Road, the North-West facing frosted windows splash diffused sunlight onto the timber floor, bouncing golden light into the hall throughout the day and retaining warmth in the brick and concrete walls. When entering the hall, people naturally drift to the edges of the room with its built-in seating, acting simultaneously as storage space for equipment and furniture, while naturally offering up the central space for activities, dancing, a speaker, or the space to enjoy watching others arrive.

When I started producing performances in the hall back in 2012 or so, I brought in lights, drapes, chairs, staging rostra: all standard equipment for black-box-theatre performances. It didn’t take me long to realize that my approach was wrong. The space pulls the performer and spectator into a common volume, the mere suggestion of anonymity is awkward when our surroundings are acknowledged. Along the walls are images of founding members, a framed letter from Lady Laura Fergusson (wife of the then Governor General) , an encased silver trowel used to lay down the first brick. The water-damaged walls are present too, revealing layers of colour and wallpaper, all visible remnants of past generations. Yet like an elderly guardian they embrace the visitor, standing alongside spectator and performer, refusing to recede into nothingness, refusing such divisions as “status” or “creed.”

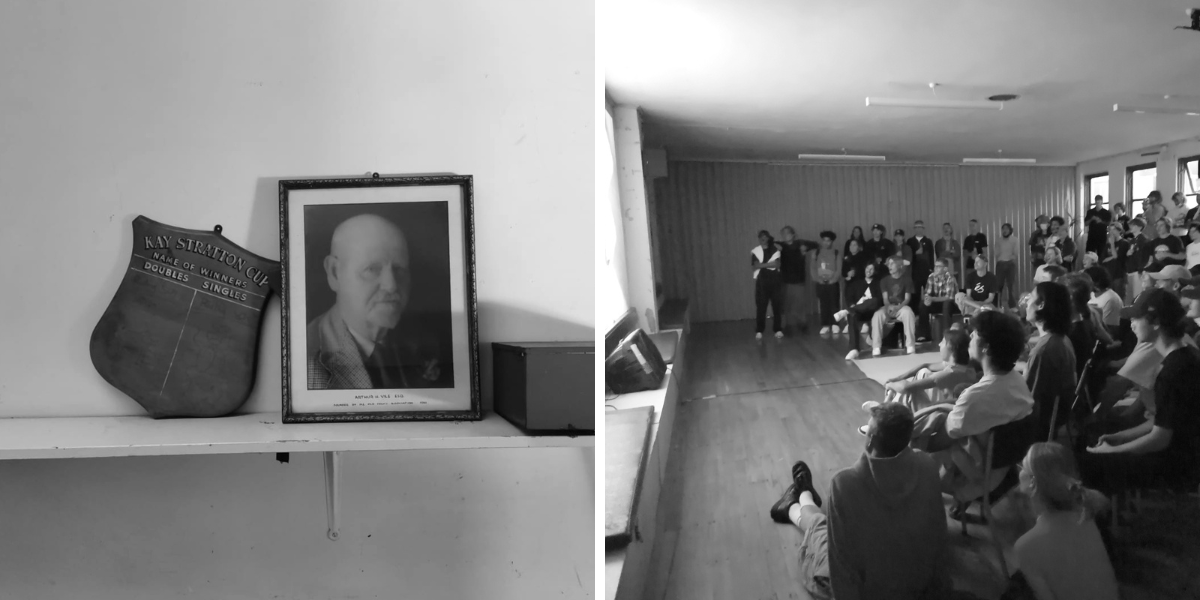

Pictured (L-R): Portrait of Arthur Vile & indoor bowls trophy; Teenagers from the local skater scene watching a video documenting their scene, 2023.

Photographs by Stephen Bain

The idea that newer is always better, commonplace in industrial design as “planned obsolescence,” presumes that the latest model will render the previous inferior. It’s part of a cultural “norm” that relates to architecture in our city too. Buildings are constantly updated, gutted of their past or demolished to make way for today’s neoliberal values. Economic activity is expected to command the proceedings and public-private partnerships are the norm. The Old Folks Hall fails at all these, obstinately refusing to clear the way for a newer model.

Festival OFA

In March of this year, a two-day festival of performance was held at the hall, Festival OFA. Around 35 artists performed 30-minute sets, with breaks for tea and coffee and a shared dinner. This was one of the most painless festivals I’ve had the pleasure to organize. Regular users of the hall were simply asked if they’d be keen to participate and provided a minimum of technical equipment. The hall was the star of the show, the performers highlighting its versatility.

Pictured (L-R): Members of Signals Pipes & Drums band march into the hall in full uniform, March 2024; Dance artist Jane Smolira performs on stage alongside 3D sculptural objects and audience members, March 2024.

Photographs by Stephen Bain

The “oldest” group (the longest-term users and average age of its members) were SIGNALS Pipes and Drums, who began working in the hall in the mid-1970s. Some are still part of the dozen-strong original group that turned up every Wednesday night to rehearse a repertoire of Scottish heritage songs, hymns, and marching tunes. At the other end of the spectrum, newcomer Jane Smolira, dance researcher and recent graduate from Unitec’s dance programme, presented an elegant exploration of externalized emotions within a sculptural field of hanging plaques. Experimental musician Ivan Mršić played a vast suite of DIY percussive instruments, many of which he had constructed in the back rooms of the hall over the preceding months. Sarah-Jane Blake embodied a distorted carnivalesque jack-in-the-box, co-opting the audience into ecologically themed participation. Formal theatre had its place too: Potent Pause Productions presented an excerpt from a Harold Pinter play. There were also fusions of music and dance with Kristian Larsen’s unique take on body and machine interface, Joe Jowitt’s maniacal sales persona accompanied by a consumerist evangelical choir, and alternative music icons Hermione Johnson and Ben Holmes blending projected home movie-style images with sporadic bursts of improvised sound.

Pictured (L-R): Participative performance by Jeff Henderson invites the audience to create a tunnel of sound, March 2024; Ivan Mršić performs with his customized percussion instrument.

Photographs by Stephen Bain

The full programme flowed organically between internal and external spaces, from one end of the hall to the other and comfortably settling into a shared space in between. On the Saturday evening, tables were prepared and a simple dinner brought spectators and performers together to eat and drink, voluntarily collapsing the division of labour to prepare, present, and clear away the food. Throughout the festival, organization was informal, allowing newcomers and regular supporters to interact.

Framework for Collective Space

With the ease and atmosphere of clubrooms, where common space optimistically asserts itself, the philosophy of collectivity permeates into social and spatial organization. The care and attention to social cohesion, fought for and fostered through endless meetings and bureaucratic organization by those original old folks, the ambiance and pragmatism of architectural reasoning, and the continued support from committee members, with all the muddled projects, the mistaken steps, the patched holes in the gib, the half-full pots of paint, and so much more… amount to the collective entity that makes up the Old Folks Hall.

As guardians, we are buoyed by those who came before us and entrusted by those yet to “discover” the hall, who will interpret this space in their own way. Our actions are pigments of ink on a lined page, protecting the bricks and mortar, yet open for the possibility of change.

Pictured (L-R): George & Janice Bain in their suburban home in Masterton, 2024; Bathroom sink at the Old Folks hall, 2024.

Photographs by Stephen Bain

My parents both turn 86 this year. There are days they’re doing well, days they aren’t doing so well, and days when you just sit on the couch next to them and watch the rain fall outside. As we contemplate our own old age, we are frequently told we should be building private palaces, homes, and family nest eggs, paid for through financial markets resistant to change for the sake of the environment or unfashionable modes of equality. Thankfully there are also those for whom a palace can never be privately owned, and whose doors reveal an open invitation to participation.

Earlier this year, I handed over the cleaning of the Old Folks Ass to the next person. No doubt they will discover their own tasks of care under the same call for collective space. We don’t rush in and finish the job, we stick with it, we oil the hinges, and, gently, we meet ourselves through the mutual challenge of cleaning one Ass at a time.

Post Note

Last year, I filmed actor Jade Daniels carrying out my everyday tasks of cleaning and tidying the space. I got him to turn on the radio, as was my habit, and by chance there was an interview with several playwrights playing on BBC World, reflecting on their relationship between the world of representation (theatre) and reality. What better way to express tasks of care and thought in a hall dedicated to performance. The resulting short film is called Cleaning the Old Folks Ass.

Notes

1

Auckland Old Folks’ Association (Incorporated), Society Rules (September 6, 1961).

2

Mary Gaudin and Giles Reid, Henry Kulka (Mary Gaudin & Giles Reid, 2022), 32.

3

Gaudin and Reid, Henry Kulka, 390.

Stephen Bain is a director and designer of independent performance in Aotearoa New Zealand. He spreads his time across experimental cross-discipline performance, producing events, and enabling community arts. Based in Tāmaki Makaurau, he holds a PhD from University of Tasmania in Public Space Performance.