Funding the Arts in Aotearoa: An Opera Perspective

Madeleine Pierard

Aotearoa’s creative landscape is something to be celebrated and valued as much as our other cultural pursuits, particularly sports, have always been. We punch above our per-capita weight in the arts, particularly when it comes to producing excellent opera singers from all backgrounds. In Aotearoa New Zealand, there is an evident and palpable disparity between the breadth of output and available funding for sustainably managing, making, experiencing and accessing art in all forms. Is there a solution to this deficiency? The route to that answer is complex—in tumultuous times, the arts are low on the list of priorities when looking at the Social Determinants of Health,1 but they’re necessary for wellbeing, social interaction, productivity, employment, and for making sense of our place in this world.

Funding Arts in Aotearoa

After seventeen years spent working as a full-time performing artist in the UK—until Covid-19 brought everything to a hiatus (and where Brexit has complicated the situation even further)—I returned to Aotearoa with my young family to take up the position of The Dame Malvina Major Chair in Opera at Te Whare Wānanga o Waikato—The University of Waikato. The purpose of my role was to develop and run a new national vocational opera training programme2 for Aotearoa’s exceptional singers, regardless of circumstance—each place is funded by donated scholarships. The vision was to develop a more comprehensive and internationally-focused curriculum than our universities are currently resourced to offer, while requiring me to continue performing internationally—a unique opportunity of a type that doesn’t exist anywhere else, to my knowledge.

Extensive commentary can be found on the subject of arts funding from practitioners, critics, and funding bodies worldwide, and the last few years have been more challenging than any in recent history for the sector due to Covid-19.

New Zealand’s response during the pandemic was viewed with admiration from the rest of the world. Looking in from the ravaged UK arts scene, the comparative support from the NZ government for the arts sector, and the creation of this role and its purpose signalled a strong culture of support, particularly for nurturing talent. This aligned with reports from agency studies indicating that the New Zealand public value the arts and our artists (which I will go into). And historically, this has been evident especially under particular governments. Government agencies have also taken steps to address imbalances and increase accessibility in the sector in recent years, sometimes successfully, by adjusting guidelines and prioritization. But does this valuing of the arts and artists translate into commensurate funding? Are the costs really being met? And if not, is the present deficiency a hangover from the pandemic or is it a more fundamental issue of perception of value?

There has been some positive change to distribution of arts funding during the last four years thanks to Manatū Taonga Ministry of Culture and Heritage (MCH) and Creative New Zealand (CNZ), but with a larger remit, the spread has thinned for contestable funding. The current New Zealand government appears to have been cultivating a more individualistic mindset than its predecessors due to their focus on the extent of national debt. So, taxation rates are unlikely to be raised enough to cover anything close to the shortfall in a sector perceived as “for the few” and “elitist,” despite very much existing in a multicultural context. Incidentally, this perception continues to hold even though, for example, tickets to see extraordinary skill and artistry from internationally-engaged Māori, Pasifika, Pākehā, Australian, and European artists in the latest production by New Zealand Opera start at $15, while the cheapest “restricted view” tickets for the next All Blacks game at Eden Park are $92. This lack of funding is despite the arts sector contributing $16.3 billion (4.3%) of the national GDP in 2023—the highest rate since 2000. In the UK, it’s estimated that there is a rate of £3 of hospitality sector contribution (for accommodation, travel and meals) generated by every £1 contributed by audiences attending performances, so the GDP contribution is likely to equate to even more than that.

Excluding the larger organizations currently funded by MCH, arts organizations in Aotearoa rely on what they can muster from CNZ grants, private donors, corporate sponsorship, grants from charitable organizations, external community grants from entities like The Lotteries Commission,3 and limited ticket revenue. The scrambling for funding by all the smaller organizations exposes the sector to an environment of territoriality due to the paucity of available sources. However, it’s clear that in “the big picture,” reflected in the 2023 Art and Creative Sector Economic Profiles report4 by MCH and the findings in CNZ’s survey New Zealanders and the Arts—Ko Aotearoa me ōna Toi5 respectively, there has never been a higher recorded GDP contribution by the arts and creative sector, and public perception of the value of the arts is increasing. The findings suggest that the sector as a whole is “thriving” despite this environment of financial precarity.

Meanwhile, the level of MCH funding to arts and culture has dropped by about 10% between 2007 and 2021. Funding “has increased over time but has not kept up with GDP growth,” and is lower than other small, advanced economies.6

Since arriving from the UK in 2021, I’ve observed that the lived experiences of individual/independent artists and those working for arts organizations paint a very different picture: even since arriving, and certainly since working here intermittently between 2006-2020 there is a noticeable decline in sustainable practices within some of the music organizations I’ve been working with, compounded by cost-saving reductions in staff numbers. This, of course, ramps up workloads for existing staff to unmanageable levels, alongside the prioritization of increasing costs in areas such as marketing. We tend to work with a sense of passion and dedication to what we’re delivering because as artists and arts administrators we’re emotionally and vocationally invested in maintaining the standard of performance that we always have. It’s inextricably intertwined with our personal kaupapa, our purpose, and identity. This is a double-edged sword—it’s perceived through the MCH’s collected data that there is no issue as the findings show positive growth, so these working conditions become normalized. I feel a strong sense that this needs improvement—but how, without additional funding?7

An issue especially relevant in Aotearoa is that funding of any genre of performing arts, or indeed any artform, shouldn’t be an “us or them” issue; the output should be accessible by all New Zealanders. We recognize—though arguably later than we should have—that organizations who have historically received less funding and recognition despite years of volunteer or iwi involvement (from grassroots to professional level) should be automatically invited to the table. Instead of anyone feeling sidelined, we should all focus our energy on raising awareness in society of the value of arts to humanity in general. Arts funding is a blanket issue, and so is redressing balance. One should not compound the other. Te Matatini, for example, is a showcase of virtuosic artistry and skill, involving huge numbers of our community. It is, and must be recognized as, a treasured source of justified cultural pride that enriches all our lives.

Arts as a Human Necessity

The fundamental issue here is that the tangible value of the arts has been globally misunderstood throughout history. Societies and government bodies have not adequately recognized or understood the value of social capital that all forms of art provide.8 Art is consumed subliminally in almost all facets of our lives, so it is harder to convince the average person of how valuable it is to them unless they are a conscious consumer who seeks out the benefits by attending shows, commissioning artworks, etc.

The essence of our humanity is deeply intertwined with the arts, elevating and motivating us, and nurturing creativity, empathy, and aesthetics. Art possesses the ability to stir emotions, foster discussion, and question established beliefs. It has the potential to motivate action, draw attention to inequality, and shed light on issues that would otherwise go unnoticed. The influence of art on our society is undeniable.

And this is important. If we ever needed to take lessons from history, it’s now. Human intelligence, creativity, critical thought, and expression are under threat from multiple fronts, including:

— A reliance on passive information consumption and confirmation bias provided by multiple sources (primarily social media),9 leading to some potentially dire economic and political outcomes.10

— A global decline in support for an educational curriculum that encourages critical thought in favour of STEM subjects intending to prioritize economic and technological growth—despite the many studies indicating the value of arts integration to both outcomes.

— The increased use of Artificial Intelligence (AI), which has obvious advantages but is an ethical minefield. It is advancing constantly and is already at a point where it’s harder for the average person to tell the difference between genuine work and an algorithmic data regurgitation that, when it comes to art, should really be considered plagiarism.11 But tech intellectual property policies around AI aren’t prioritized to do much about it, as the economic benefits to tech investors are prioritized over moral considerations. The legal landscape that surrounds AI-generated content is understandably sparse as yet, though many universities have explicitly banned its use for exegesis writing at least.

— The violence and loss in Ukraine and Gaza, and the very real physical threat to human life, is engendering a global sense of hopelessness, and resulting in an economic knock-on effect which has contributed to a crippling downturn for many economies, not to mention the devastating impact on the climate.

These are global events that we’re all aware of which, in various ways, contribute to a decline of public and government perception of the necessity for state support of the arts. There are very few exceptions to this—mostly in Europe. Estonia, Latvia, Hungary and Iceland are prime examples,12 funding the arts at the highest proportion of government expenditure in the OECD. The high taxation rates required to do this render it unpalatable to individualist-leaning societies.

We know how vital the arts are to every fibre of our being, allowing us to understand and express our human complexity and existence while also—and this is especially important—nurturing interaction, collaboration, passion, inspiration, connection with our past, a sense of community, and collective consciousness that is in considerable decline in our modern lives.

As well as being a factor that should be considered as part of the Social Determinants of Health, access to the arts is a public health issue. Mental health is in decline — we see the data13 showing mental health issues have increased due to social isolation and an online world that is all-consuming, always available and instant. Evidence supports the necessity of art to positively impact neurological processes: “There is increasing evidence in rehabilitation medicine and the field of neuroscience that art enhances brain function by impacting brain wave patterns, emotions, and the nervous system. Art can also raise serotonin levels. These benefits don’t just come from making art, they also occur by experiencing art. Observing art can stimulate the creation of new neural pathways and ways of thinking.”14 This, in turn, increases productivity, economic growth, and stability. But the message doesn’t seem to adequately reach the places it needs to.

In the UK, where I spent much of the pandemic, having lived and worked there as a full-time performing artist for the previous sixteen years, the sanity of every person relied on the consumption of art wherever they could find it: digital art and storytelling in gaming, emotionally uplifting or epic movie soundtracks, live or studio recordings of music of all genres, extraordinary animation, theatre performances being made available online, books that we’d been meaning to read for years moving us to tears… oh, and Netflix.

Pictured: Fatima’s Next Job Could Be in Cyber, HM Government UK, 2020.

Yet the UK government was actively campaigning for artists and other “non-essential” workers to retrain in “more useful” employment, like cyber security. So, as we sat there and observed our craft being made available and shared for the greater good, thus feeling the value of what we do for humanity more than ever before, buses were sporting the ad above. The ad was conceived and distributed as a partnership campaign between Cyber First and Her Majesty’s Government in October 2020 and was very quickly retracted due to pushback from the public, who very rightly considered it to be in poor taste given that the sector had been obliterated. And yet, the product of these artists was being consumed in every household, often for very little or no cost.

In 1945, when the world was suffering in the wake of World War II, UK political parties recognized the need to prioritize arts education and funding to assist with the re-establishment of culture and collective recovery:

“No system of education can be complete unless it heightens what is splendid and glorious in life and art. Art, science, and learning are the means by which the life of the whole people can be beautified and enriched.”

— Winston Churchill’s Declaration of Policy to the Electors, 194515

“And, above all, let us remember that the great purpose of education is to give us individual citizens capable of thinking for themselves. … By the provision of concert halls, modern libraries, theatre, and suitable civic centres, we desire to assure to our people full access to the great heritage of culture in this nation.”

— [UK] Labour, Let Us Face the Future, 194516

Conversely, in Aotearoa, following Covid-19 and anti-government sentiment during the pandemic, I’ve seen a lot of public commentary surrounding arts funding, suggesting that it is a frivolous use of taxpayer funds during a cost-of-living crisis. This doesn’t align with the findings of CNZ’s survey New Zealanders and the Arts—Ko Aotearoa me ōna Toi,17 which found that a majority of New Zealanders recognize the importance of the arts to society. And so unsurprisingly, money has the only tangible value that all societies recognize, which is why large-output financiers are comparatively remunerated so vastly, for example. Society in general values that skill 100% more than a concert pianist for example, despite the likelihood that the latter studied for double the amount of time of the former and is a rarer virtuoso by comparison.

Opera? Really? Why?

On the other side of the coin (no pun intended) the financial support of an artform like opera is a harder sell than some other artforms. It is eye-wateringly expensive. New Zealand Opera tours most of its mainstage productions with an average cost of over $2 million.18 LA Opera goes as far as to explain these high costs in a blog post, The True Value of Opera. While not terribly in-depth, it explains some of the reasons for these high costs:

“As a nonprofit, our mission is not to make money, but serve the community and keep grand opera alive in Los Angeles. However, live opera performances are extremely labour-intensive and therefore very expensive. On average, LA Opera spends $6,500 each hour our stage is in use for technical work, rehearsals, or performances. Depending on how intricate the set design is, we can spend up to US$1.5 million on the physical production alone—not to mention making sure that the artists and artisans working both on stage and behind the scenes (who have trained for years to perfect their craft and bring their creative talents to our stage) are paid fairly and can make a living wage. You may be surprised to learn that ticket income covers less than 50% of our costs – the rest is paid for through the generosity of donors, small and large, who value the arts.

“Is all of this work and attention to detail necessary? We strongly believe it is. This level of dedication is what separates art from simple entertainment, and to profound impact. David Brooks says it best in his New York Times article “The Power of Art in a Political Age,” when he said that art and beauty “prompts you to stop in your tracks, take a breath and open yourself up so that you can receive what it is offering, often with a kind of childlike awe and reverence.””19

But there is so much more to the true value of opera.

At a basic level, what excites me is how few people realize how unique it is that an opera singer’s highly-trained vocal technique enables the vibration of tiny vocal folds with a perfect amount of air pressure to be heard over a 60-piece symphonic orchestra in a 2500-seater hall WITHOUT AMPLIFICATION. It still blows my mind after all these years. But also, it is comforting to know that access to this “no-filter” expression of human emotion of desire, loss, hatred, desperation will never be able to be replicated by AI, certainly not in a live context. I honestly believe that if more people realized this, they’d be more interested in coming to check out how it works.

At the next level, there is immediate connection with an audience that comes from a deep, visceral place (it has to). This, in combination with extraordinary music, epic storylines, and powerful forces in the pit and on stage, means that audience members can connect and engage with what’s happening on stage in a way that is far more intimate than an amplified musical offering or movie. It often changes them in that moment, helping them to understand themselves and their own emotional responses more fully—as well as others’, as David Brooks mentioned in the New York Times article above.

My favourite aspect of opera is the collaborative aspect of the artform. Every moment on stage is created by a host of collaborators: set designers, painters, costume designers, costume construction, set construction, tech crew, stage management, lighting designers, a professional chorus of around 30 singers (usually), a full orchestra, music staff, music library staff, surtitle operators, sound engineers (for orchestra foldback in the wings so the singers can hear the orchestra), makeup and wig artists, actors, dancers, prop makers, company admin and operation staff, front of house staff, and of course, the stage director (and assistant director) and conductor (and assistant conductor). Opera productions employ the largest range of skilled professionals in any live performance art form, contributing to a remarkable experience for the audience and company alike, and which provides employment opportunities for communities.

At yet another level, in Aotearoa we have a unique example of how incorporating opera into a community context, particularly at school age, has a positive impact on community wellbeing. Participatory opera programmes have long been championed as a successful model for impacting the community, and producing opera in partnership with communities can drive a range of social impacts, from health and education equity and well-being, to deeper, broader community engagement. These benefits have been well documented, particularly in Europe and the UK.

Project Prima Volta (PPV), the flagship programme of Prima Volta Charitable Trust (PVCT) was established in Napier in 2013. It supports 30–40 teenagers annually in a free, intensive programme that trains their voices, helps them develop an understanding of opera, and supports them to put their new insights to the test. The programme takes place each summer, through a partnership with Festival Opera, where participants take up the role of the Dame Malvina Major Foundation Festival Opera Chorus. PPV Junior was established in 2017, offering similar support to Tamariki from the age of eight.

Says Prima Volta Charitable Trust Co-Founder Anna Pierard:

“Our vision for wellbeing through music was launched in 2014 in Whakatu, Te Matau-a-Māui, in response to a rising mental health crisis plaguing rangatahi, which tragically included a cluster of youth suicides. PPV was the outcome, the response to a problem of disconnected teenagers whose value was not being affirmed and whose voices were not being heard. The vision is unique when compared with other youth development organizations that focus on the removal of practical barriers to access support, job pathways, or further education, in that it takes the rarified, professional, and high-art world of opera, and welcomes beginner teenage singers into this aspirational environment—to learn, to be mentored by experts in their field, and to participate in the final creative effort. The practical obstacles are removed along the way; the programme supports participation by providing free transport and food.

“In 2021, the programme commissioned a report from ImpactLab to better understand their SROI (Social Return on Investment). For every $1 invested in PVCT, the community return on investment is $2.45. The programme data was measured against Treasury's Living Standards Framework and charts significant health, jobs, and earnings impacts. Our community continues to support our programmes because they see these young people achieving amazing things beyond their time in the programme.

“In 2018, the launch of PPV VoiceLab, our research and development programme, really focused our ambitions. Through this programme, we have worked with other music education specialists and consultants to understand the ways that the artform can help to address non-musical challenges in educational settings. Our interest is not in what our community can do for opera, but what opera can do for our community.”

These remarkable programmes, in addition to being such a success in the local and wider community, have produced some of Aotearoa’s most exciting young artists, many of whom have gone on to study voice at tertiary level. Six of these artists have been or are currently with us at Te Pae Kōkako—The Aotearoa New Zealand Opera Studio (TANZOS).

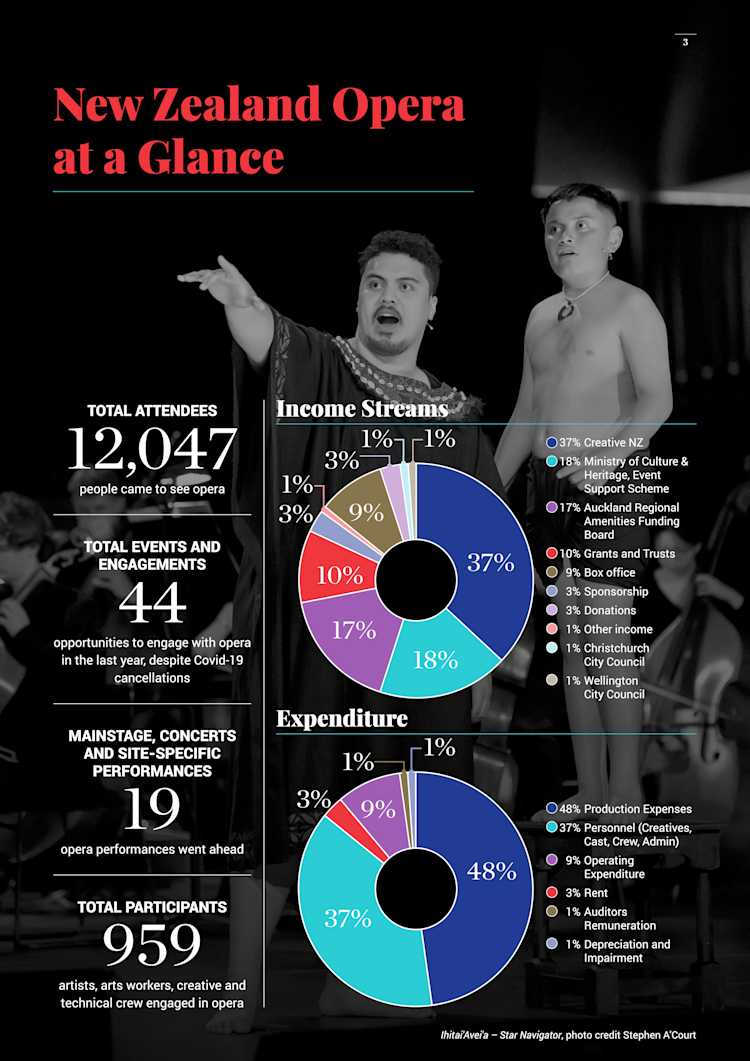

Pictured: New Zealand Opera at a Glance Statistics, NZ Opera Annual Report, 2022.

PPV and its sister organization, Festival Opera, have amassed meaningful engagement and support from local and national funders, including CNZ, through tireless development partnership. NZ Opera is the highest-funded arts organization by CNZ (the other major arts organizations are funded at Ministry level by MCH) and still relies very heavily on patronage and grants from other sources. There is a solid administrative infrastructure at NZ Opera too, but even there I see how stretched they can get at times. A person in a very high leadership position of a New Zealand arts organization, who had transferred from the business sector, once told me they’d had no idea how much more stressful working in the arts would be, how all-consuming and constant the work often was, and how the scrambling for funding and meeting targets was by far the most stress-inducing aspect of the work. No wonder so many of us are at the point of burnout.

Pictured: Training Opera Singers in Aotearoa—a Flowchart, Madeleine Pierard, 2022.

Funding Is Stretched to Its Limit. What Can We Do?

Our national non-government funding organizations are already showing a high level of investment and confidence in whatever capacity they can. The Dame Kiri Te Kanawa Foundation and Circle 100, for example, do a stellar job of fostering talent at the point of heading overseas, and continue to nurture those artists in a meaningful way. Foundations such as The Dame Malvina Major Foundation, The Freemasons Foundation, Foundation North, Friedlander Foundation (and many more) and private patrons are staunch supporters are generous with the breadth of projects they fund within New Zealand.

TANZOS is the brainchild of Dame Malvina Major. When I was working on how we might best meet the needs of the sector at post-tertiary training level, I drew up a flowchart20 showing the various stages of opera training from primary school level. The flowchart illustrates the main providers of that training and involvement. This was a means of trying to understand it myself, and where we should fit, but also to help explain it to others who might think there is too much duplication of providers in the sector. There isn’t. I realized very quickly, somewhat astonished, that the Dame Malvina Major Foundation (DMMF) funds a proportion of every single stage of development for opera talent. I don’t think there’s more we can ask of our existing funding bodies.

But we also can’t ask for a higher proportion of government revenue expenditure—I don’t see how that would be achievable in the current political and global environment, and I can quite understand the quandary of prioritization of funding distribution.

There are examples among generous individual donors who give invaluable quantities of money to specific projects in our sector, whether through organizations as listed above or through individual philanthropy. While I hope that this culture long continues, the arts are sometimes overly reliant on major donors like the convicted and now-disgraced James Wallace, so some of this reliance has been harmful and problematic. That said, we could argue a similar moral dilemma for the use of Lotteries Commission funding, 42% of which goes into the CNZ pot.

Instead, I would argue that high-profit corporate organizations could be more meaningfully encouraged to contribute to the happiness and culture of our motu, just as they do with climate change policies for the greater good. New Zealanders have a history of looking after each other (well… for the most part), and we have a major creative taonga that we need to protect. I hope this is already being discussed and progressed; I know several General Directors of large arts organizations at least are involved in these conversations at government level, which is encouraging. And I would also hope there would be a case for proposing increased tax incentives from the government for corporate or individual giving to the arts.

Named corporate sponsorship for the arts is not new, and was especially prevalent under our former Prime Minister, Rt. Hon. Helen Clark, following a significant boost in profile for the arts sector. When I was in the New Zealand Youth Choir in 2000-2002, it was the TOWER New Zealand Youth Choir, sponsored by Tower Insurance. New Zealand Opera had named sponsorship from National Business Review (NBR) and its chorus was the Chapman Tripp Opera Chorus. The latter was thanks to the efforts of Alastair Carruthers CNZM,one of our most involved and dedicated contributors to arts governance in Aotearoa. One suggestion for why named corporate sponsorship has fallen out of favour is the generational shift at leadership level; art (except visual art, perhaps) is simply not valued as a philanthropic interest as it was.

Even then, the collective positive impact wasn’t fully understood. André Chumko, a senior reporter for Stuff and formerly for The Post and Sunday Star Times, touched on this subject brilliantly in an article from August last year.21 Interviewing Jo Blair (The Arts Foundation Lead) about the period during Clark’s leadership, he quoted:

“To have a healthy funding ecosystem for the arts across government, philanthropy, and business, brands needed to step up and lead, said Blair. But even then, some brands like Ockham Residential funded the arts more out of generosity and the belief the arts could be transformational for health and wellbeing.

“The arts were forced to rely on contestable Creative New Zealand grants and other money through lotteries and the NZ Community Fund because of the lack of commitment from businesses. If corporates were willing to think long-term, they could help deliver something “much bigger” and more valuable to society, said Blair.”

Chumko also quoted these wise words from Georgia Mahaffie of One New Zealand, who partner with The Arts Foundation to fund the Arts Foundation Te Tumu Toi Laureate Awards. They support my point above about subliminal consumption of the arts:

“Art in all its forms, is incredibly powerful and is influencing us every single day whether we realize it or not. A bit like the Devil Wears Prada scene with the blue sweater, you might not think it but you’re a part of it already. That in itself is a huge barrier the Arts Foundation [is] trying to break down. But, especially in time[s] of great change, art can capture and express what it felt like to exist in a particular time, so there’s no time like right now for the arts to shine and for corporates to get involved.”

I have been wondering how best to go about this. The stretched development departments of organizations that are lucky enough to have one are already working at capacity, so who assists with establishing these partnerships? There are organizations like Honoco that work on strategic partnerships from the corporate side, including philanthropy, but I am struggling to find examples of affordable support for arts organizations in this way, other than direct networking. Of course, there is also the fact that meaningful relationships with interested parties are more successful with direct engagement from those working on the cause, as the emotional and personal connection is important. But who is advocating for the marketable value of arts sponsorship? If I weren’t so stretched in my current role, I’d definitely put my hand up.

What I see that is missing is a measure of influence and understanding of the value of arts to society from leadership or positions of influence since Clark’s time. I believe support from the government in the form of higher tax incentives for high-profit entities to fund the arts, for example, would inspire a level of confidence for corporate investment and encourage the culture of contribution to the wellbeing of the society they are part of. And that is good for everyone.

Notes

1

Gordon-Nesbitt R., Howarth A., The arts and the social determinants of health: findings from an inquiry conducted by the United Kingdom All-Party Parliamentary Group on Arts, Health and Wellbeing. Arts Health. 2020 Feb;12(1):1-22. doi: 10.1080/17533015.2019.1567563. Epub 2019 Jan 24. PMID: 31038422.

2

Te Pae Kōkako TANZOS—The Aotearoa New Zealand Opera Studio, now in its second year of operation. https://www.tanzos.org

3

Durrant, Martin, 'Arts funding and support', Te Ara—The Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/arts-funding-and-support/print (accessed 16 June 2024).

4

5

6

Sohanpal, Nihal, Toi Mai (Workforce Development Council) Research Note: Government Expenditure to the Arts and Cultural Sectors Government expenditure to the arts and cultural sectors | Toi Mai:

“Overall MCH funding designated to ‘arts, culture and heritage’ has declined from 81% in 2007 to 71% in 2021. Non-Departmental Expenses for ‘arts, culture and heritage’ dropped circa 12 percentage points to 64.88% in 2021 (76.25% in 2007).”

“Non-Departmental Output Expenses, which most commonly fund Crown entities and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as Creative New Zealand, plummeted nearly one third to 48% in 2021 from 67.3% in 2007.”

7

In the tertiary education environment, I have experienced this lack of work-life balance, which requires another, probably even longer conversation—but I am not the voice that needs to be heard in that area as Te Pae Kōkako TANZOS (The Aotearoa New Zealand Opera Studio) at The University of Waikato is donor-funded and therefore not subject to the same structural constraints as other university arts programmes. Certainly, the state of the arts curriculum in education from primary to tertiary level in Aotearoa is somewhat bleak.

8

Feldstein, Lewis M.; Cohen, Donald J; Putnam, Robert D. ‘The Arts and Social Capital’ Better Together: Restoring the American Community – Report from the Saguaro Seminar on Civic Engagement in America. John F. Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University THE ARTS AND SOCIAL CAPITAL

9

10

11

12

OECD (2022), The Culture Fix: Creative People, Places and Industries, Local Economic and Employment Development (LEED), OECD Publishing, Paris https://doi.org/10.1787/991bb520-en “<In 2019> Estonia, Latvia, Hungary, and Iceland spent almost 3% of their national government expenditure on cultural services” ‘Overview of government and household spending on culture in OECD countries’ 5. Public and private funding for cultural and creative sectors see comparisons listed in Government expenditure to the arts and cultural sectors | Toi Mai

13

14

https://acrm.org/rehabilitation-medicine/how-the-brain-is-affected-by-art: “Any type of creative expression allows you to imagine new ways to communicate and engage with the world, as well as engages the brain’s neuroplasticity, helping patients recover from things like traumatic brain injuries or stroke.”

15

Churchill, Winston, 1945 Conservative Party General Election Manifesto

16

Attlee, Clement, “Let Us Face the Future”, 1945 Labour Party Election Manifesto

17

18

19

Post by LA Opera, ‘The True Value of Opera’ (author uncredited) https://www.laopera.org/discover/la-opera-content/new-blog-post-27

20

View the flowchart in larger format here: https://www.tanzos.org/_files/ugd/c5cc4c_0c9c4ad8e91d428eafaebeda5e35beb1.pdf

21

Chumko, André, What Happened to Corporate Arts Sponsorship in New Zealand? stuff.co.nz, August 2023. What happened to corporate arts sponsorship in Aotearoa? | Stuff

Soprano Madeleine Pierard grew up in Āhuriri and studied Biomedical Science, Composition, Musicology, and Performance at VUW before specialising in opera and living in London for 16 years. Madeleine is a co-founder of SWAP’ra (UK), Director of Te Pae Kōkako—TANZOS in Kirikiriroa, and is maintaining a high-level international opera career and three small children.