Questions for

Sriwhana Spong

Tell us about yourself right at this moment: geographically, musically, artistically, personally…

Right at this moment, I’m sitting in my studio at Gasworks in London. Outside the window, an extensive new development is rising. Behind me, Alice Mendelowitz, who I share the studio with, is painting. On the windowsill is a postcard of the Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore—a Benedictine monastery down the hill from Chiusure, Siena, where I spent last summer on residency—a porcupine quill, and a dead frog flattened by a car wheel, both of which I found on walks in the area. I met Ugo at the monastery. He makes these drawings in his limited spare time, which he describes as “disequilibriums.” A brother at the abbey makes wooden frames for them, which he roughly gouges lines into, and he also paints on the glass using homemade tinctures, iodine solution (he used to work in the abbey’s hospital), and bleach. His drawings are made with coloured pencils and comprised of geometric shapes, the traced outlines of objects from around the abbey, frottage, and text: things that are close at hand. I asked if he would like to collaborate on a painted film, but he said our work is unrelated. My understanding is that when Ugo draws, God moves through him. The act of drawing becomes like an act of prayer. But when I make, what moves through me? He said he would be happy to meet up and talk during my time in Chiusure, and so we did. I talked about how I don’t believe in God, and he talked about how he found his vocation after working as an architect in Naples. One day, I bumped into him as I was exiting the abbey’s pharmacy with a tincture for anxiety. I don’t think those work, he said. Follow me. So I followed him through a locked gate and down the side of the abbey. Stay here and don’t move, he said, then disappeared through a side door. Ten minutes later, he emerged with a latticed cherry pie and a packet of valerian tablets. These will actually help you sleep, he said. When I left Chiusure, I made him a drawing in exchange for some sketches he had given me. One of these had correction fluid covering an entire circle. I asked if he had made a mistake or if it was deliberate. He said, it could be a mistake or it could be a reflection.

Pictured: Ugo showing the Amant Siena residents his drawings at the Abbey of Monte Oliveto Maggiore, 2023.

Photograph by Sriwhana Spong

Pictured: Ugo with his works at Amant Siena, 2023.

Photograph by Sriwhana Spong

Thinking of Ugo, I’ve been making drawings in the studio by tracing around a coin. It’s early days, and I don’t know if they will work or not, whether they will ever leave the studio. The action is repetitive, and as I work, I let my arm smudge the drawing, so there is a rhythm of lines and smudges, structure and vapour. What moves in me as I make them? I’m not sure, but their repetitive action means I can think about the other works currently finding shape around them: a film about teeth filing and sculptures based on the statuette of a frog I saw at the British Museum in a display case titled “Emergence of the gods.”

How did you come to art/making?

When I was nine, we moved to England for six months and my parents became friends with a painter. He made these really thick, brightly coloured acrylic paintings into which he stuck everyday things like straws and plastic lids from McDonalds cups. I remember thinking they weren’t very good but desperately wanting to touch them because the paint was so dense and oozy. So I did, and he saw me and told me off. I was mortified, but now painting had my attention. When I was eleven, I visited a friend’s house after school. There were a number of Tony Fomison paintings high up on the wall, and they gave me a real sense of unease. This is all to say that for me, strange feelings accumulated around art experiences, which made me curious, kept me interested. We often hear talk of love, one does something because they love it, etc. I think art-making for me has always been connected to fear—thinking here of its Proto-Indo-European root per “to attempt, try, research, risk.” I guess art felt (and still does) like a place where one could take risks, attempt things, a place of strange feelings, where nothing is stable and all is to be dared, a bit like love after all perhaps?

When/where/how did you encounter dance?

Growing up, I had these old ballet annuals that had belonged to my Mum, which really consumed me. They are where I first encountered modernist sculpture and painting—through photographs of props designed by Noguchi for Martha Graham, stage sets by Rauschenburg for Merce Cunningham, and costumes and backdrops by Goncharova, Picasso, Laurencin, and Matisse for the Ballets Russes. The dancer I was most drawn to was Nijinsky, especially the photographs of him as the faun or the spirit of the rose. I was also drawn to the (rare) stories about dancers of colour, like the Tallchief sisters, Maria and Marjorie, who were of the Osage Nation. Maria Tallchief became the first prima ballerina in the United States.

Pictured: Vaslav Nijinsky as The Rose in Le Spectre de la rose, 1911.

Public domain photograph

I was raised in a Pākehā family, but have Indonesian heritage, which created a family language of holes, gaps, secrets, things left unvoiced. Dance to me echoed this language, so I instantly felt at home in it. Slipping into the body of the music, a character, a costume, a choreography, was also a means of escaping, a useful defence mechanism at the time. I started classes quite late, at seven, and then that was my life for many years.

How did you move from painting to an expanded conception of art-making that encompasses film, sound, and performance?

I never really just focused on painting. I also studied sculpture and photography at high school. But I think my dance experience, where you are dealing with tempo, time, sequence, other bodies, a mirrored room framing and reflecting images obviously resonates with film. When I was around eleven, I saw a performance at the Aotea Centre where a French soloist danced alone in silence. You could hear her feet, her breath, the hum of the lights, and the rustling of the audience. It was a more conceptual way of thinking about dance than I had previously experienced—something more akin to Cunningham’s approach—and it really stuck with me, made me aware that there was something beyond the classical ballet I was familiar with. I went into the Intermedia department at Elam, headed at the time by Phil Dadson, where we explored sound, film, video, and performance. It was super experimental and collaborative, utterly chaotic, and ultimately a lot of fun. More recently, a tutor on my MFA course commented that I make films like a painter, so I’m not sure I entirely moved on from painting.

What draws you to the mystic composer Hildegard von Bingen (and other mediaeval female mystics)?

On a few occasions, it had been pointed out to me that my work was quite “mystical,” and not in a complimentary way. So at a certain point, I decided to explore what we mean when we say “mystical” because, to me, it seemed like a vague term and one that was being used to indicate toward something in my work that shouldn’t have been there, something that was being, through these comments, disallowed. Michael Kessler and Christian Sheppard, in trying to edit their book on essays titled Mystics, admit that “the more lucidly we describe mystics… the more elusive it seems,”1 and I found that to be the case. It’s a slippery subject. So I became interested in Michel de Certeau’s method of “studying” mysticism. He constructs an interdisciplinary frame composed of four different areas of enquiry, four different approaches: contemporary eroticism, psychoanalysis, historiography, and the literary genre of the fable. This frame produces a space in which his subject might appear. However, de Certeau admits the impossibility of getting much closer to his subject: “It is a form whose matter overflows. At least this explanation of my “interests,” in circumscribing the framework within which a representation is to be produced, will allow us to see the way the subject crosses the stage, escapes, and goes beyond”2—an overflow he likens to painting.

De Certeau’s method obviously made me think of film-making, and it seemed to offer a way of approaching a subject that would allow it to cross the film, pass through it, and escape, leaving a trace in the silver halide crystals and animal gelatine of celluloid, which might retain something of the thing being followed by the filmmaker. De Certeau also likens mystic writing (we are talking here of practices specifically from within a Christian tradition, because mystic practices are local practices and these were local to him), as “scripts of the body,” which translate the impressions a religious encounter makes on the mystic’s body. This process of translation, the struggle to bring the unverifiable into language, generates particular and inventive practices that draw largely on experiential knowledge. I have begun to think of my films as “scripts of my body,”3 which document less a subject and more my body, trembling at twenty-four vertebrae a second, as it moves toward another.

Calling Hildegard a mystic is for some historians controversial, but for de Certeau, the mystic engages in a practice that opens up a journey which transforms life itself, and I think this is something Hildegard was constantly attempting to do through her music compositions, writing, research into medicinal plants, the illustrations she directed of her visions, and her Lingua Ignota, a secret language she says she received. Something like a secret language may seem entirely pointless, and it has been described as such, but there are many things operating in Hildegard’s Lingua Ignota. Looking at her glossary of over a thousand nouns, you get this immediate sense of the particular things that surrounded her, what was important to her, what she focused on. There are no adjectives or verbs, so it offers a very direct sense of her environment, its materiality. She apparently inserted her nouns into Latin syntax, stealing its adjectives and verbs to allow her nouns to move—a disruption and an infection of Latin, the official language of the Church at the time, through a secret and personal language. It’s also been conjectured by various historians that she shared this language with her sisters, so it might also be thought of as a language by a woman for women. By giving a new name to something—a fish hook, a candle, a running sore, a raven—she approaches it anew, sees it afresh. She dusts things with her tongue. It would also be an entirely useless language for trade because no one would know what you were trying to sell them.

I see these mystic practices as radical in that they opened up spaces of discovery and enjoyment for women (those privileged enough to be able to engage in them) within the patriarchal and ecclesiastical structures at the time—and some were burned for it. To me, many texts—poetry, songs, mystic writings, etc.—can be considered living documents, moving within the spaces and bodies in which they are spoken, sung, and heard with something (sometimes) still to say.

Can you talk a little about your practice of collaborative instrument-building, and perhaps relate that to instrumentality generally?

The series of, currently eleven, instruments in my yet-to-be-titled orchestra was initially sparked by reading Andrew Clay McGraw’s book Radical Traditions: Reimagining Culture in Balinese Contemporary Music, in which he writes about how each gamelan in Bali has a unique tone developed over time, which represents what he describes as “an aural watermark for a community.”4 I was really struck by this idea that a place and a community would have its own sound, and it made me wonder what sound a more diasporic sense of place, like mine, might have. The first two instruments in the series are based on paired metallophones from the gamelan. Each pair is made up of identical notes but pitched a few hertz apart, so that when the notes are struck together, an oscillating wave known as ombak is formed. Composer-performer Antonia Barnett-McIntosh wrote a piece for Instrument A (Antonia) and was the first person to play it. During the performance, she spontaneously took out her metal earrings and placed/hung them on the aluminium bars, which created a shimmering rattle as she played. Each instrument is named after someone who has been important to its development or to my work in general. So the orchestra inscribes a community of interlocutors, the things I am exploring at the time each instrument is made, and the place/show/gallery each one is made for. Like the gamelan, they are largely percussive.

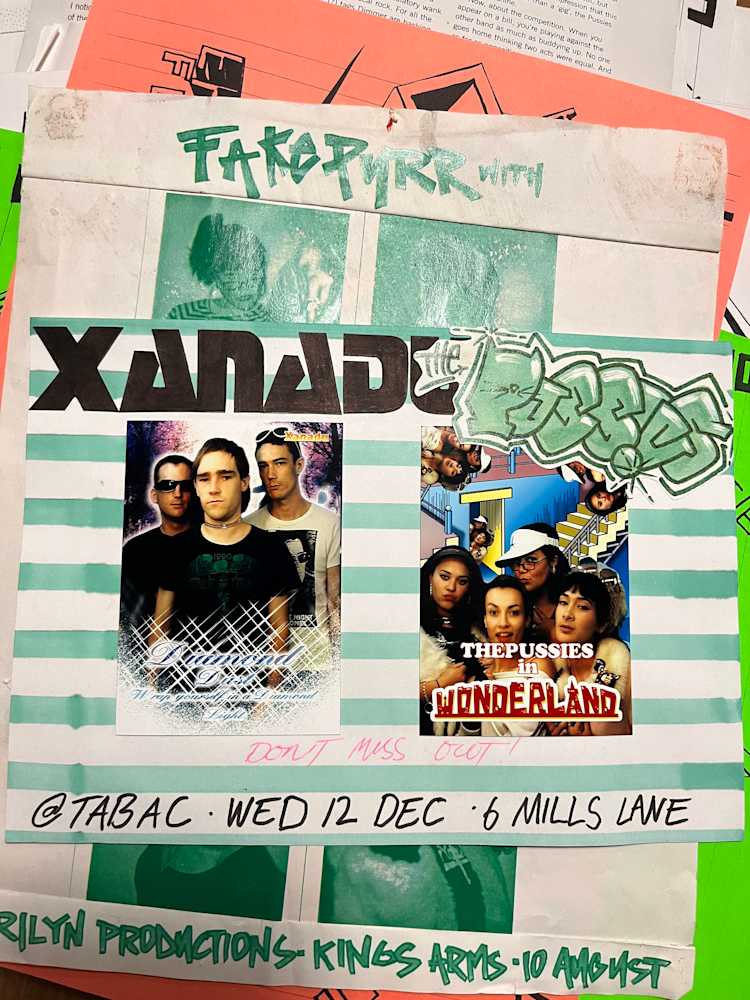

Pictured: Poster for Xanadu and The Pussies gig, 2001

I’m not a sound artist or a musician, although I was in a band called The Pussies in the early 2000s, with Melanie Tangaere Baldwin, Pritika Lal, and Jessica “Coco Solid” Hansell, all of whom I met in high school. None of us, apart from Jessica who played the keyboard, really knew how to play our instruments, but it was, for me at least, a way of exploring through music our experiences as women of colour from different mixed heritages. We had a song called “Half Breed,” which featured the line, “I’m a half-breed baby, and I mean what I say, I ain’t full-blown nothing, but I’ll blow you away.” It still runs through my head sometimes, like a mantra. The Pussies, for me, was a really important way of bringing the complexities of a dual-heritage experience into language, and not just any language but a language we were writing together, and not knowing what we were doing was a vital element.

Pictured: Opening performance by the Coolies (Stefan Neville, Tina Pīhema, Sjionel Timu). Installation view: A hook but no fish, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth, 2018. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Lett.

Photograph by Samuel Hartnett

Tina Pīhema and Sjonel Timu from the punk band The Coolies were a huge inspiration at the time (still are), and I invited them to play different configurations of the orchestra at the Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, Ngāmotu, the Auckland Art Gallery, Tāmaki Makaurau, and Spike Island, Bristol. These performances open up a space in my work for other practices, voices, and visions in ways I can’t predict or control. It’s important to me that when I invite people to play the instruments, the performers have the freedom to work with them how they wish—for example Frances Libeau used a bunch of gorse as a brush on Instrument C (Frances), which is named after them, when they performed at the Auckland Art Gallery. The instruments range from bronze objects, such as round bells filled with items collected from the city of Istanbul, to long brushes made of plastic netting and hundreds of bobby pins.

Pictured: Performance by Frances Libeau. Installation view: The painter-tailor, The 10th Walters Prize, Auckland Art Gallery, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Lett.

Photograph by David St George

Pictured: Hiçbir bedel, hiçbir koşul istemeden – Undoubtedly, I am a high-frequency energy, performed by Kardelen Savcı, Ahmet Berk Tuzcu, and Bengisu Üstay with Instrument I (Sevgi and Bengisu) (2022), bronze, plastic bottle caps, cymbals, terrahertz stones, antique keys, goat bells, jingle bells, decorative bells, clapper bells, wooden juniper beads, rocks, shells, earrings, pebbles, glass marbles. Installation view: Istanbul Biennale, 2022. Performance made in collaboration with Bengisu Üstay. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Lett.

Photograph by David Levene Images

Expand upon your experiences of how art institutions work as sites for performance.

It’s a very different experience to being on a proscenium stage. When I performed on stage as a teenager, I used to have this feeling that all the energy in the room was being drawn into the vortex of the dance, which is quite an intense experience—and I’m doing a terrible job of finding words to describe it. In this moment, one became really aware of the elasticity of space and time. In a gallery, that energy vortex can be more diffuse, but it does allow for nearby works and activities—people entering and exiting, or looking at other works—to enter the performance. In a gallery, you’re in conversation with the other pieces in the surrounding spaces: sound bounces off sculptures, photographs, and monitors, or is absorbed by fabric works or canvas paintings, which is something I do really like.

How is writing about your work important to you?

When developing a new work, writing is a tool I sometimes use. I think of my process as a metabolization process, where research is left to dwell in the particularity of my body for a period of time, engaging with my day-to-day life, until images and ideas begin to bubble to the surface. It’s a way of involving the scientific and the intuitive, the experiential and the studied, waking life and dreaming life as entangled approaches toward making. I particularly enjoy writing because I’m always surprised by what emerges, and I find the distance or separation that words can provide to be particularly helpful.

Which music/sound/performance practitioner holds your interest at the moment?

I recently worked with James Rushford, an Australian composer and performer, whose work has been described as “haunted Jacobean ASMR.” He sometimes plays a portative organ, or organetto, which originated in the twelfth century. The organetto has a row of flue pipes and a set of bellows and can sit on the performer’s lap. This positioning makes the body of the musician an important element in the composition, and the surrounding air being drawn continuously through the mediaeval instrument creates an interplay of chronologies and anachronisms. We were on residency together in Siena, and I was lucky enough to hear him play his organetto on a few occasions. James composed a piece for my most recent film Badlands, which is one of the few times I have choreographed the image to the sound—usually I tend to have the sound designed once the edit is complete. Because of this, it is my most dance-like film, and as it was partially fed by the work of Ernesto de Martino and his writings on Southern Italian magic rituals and the tarantella, this approach made the most sense.

What gives you hope?

Fungi.

Pictured: Badlands (2023), video stills. Courtesy of the artist and Michael Lett.

Notes

1

Michael Kessler and Christian Sheppard, eds., Mystics: Presence and Aporia (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), x.

2

Michel de Certeau, The Mystic Fable, Volume One: The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries, trans. Michael B. Smith (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 4.

3

Michel de Certeau, The Mystic Fable, Volume One, 81.

4

Andrew Clay McGraw, Radical Traditions: Reimagining Culture in Balinese Contemporary Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2013).

Sriwhana Spong is an artist who works across film, sculpture, and performance. Recent exhibitions include Luzpomphia, Michael Lett (2023); the 17th Istanbul Biennial (2022); The Poem is a Temple, RIA Live Art Commissions, The Roberts Institute of Art, London (2021); Ida-Ida Spike Island, Bristol (2019); A hook but no fish, Govett-Brewster Gallery (2018).