Improvisation Within a “Liveness” Ecology…

Andrew McMillan

Am I beginning with a response, a reflection, or an idea? Or a formulation of thought and action through the interaction between all of these?

I shall ramble.

But, have I/we started yet? I guess so, because words have formed on the page. I am engaged with writing, and you are hopefully engaged with reading, questioning, and continuing to read and question until the end.

In this article I will present discussion points, proposals, provocations, or probes to discuss how I feel my existence within an improvised performance materialises, and how that relates to:

Liveness:

“the quality or state of being ‘live’ e.g. the reverberant quality of a room”1

“the state or condition of being alive”2

Although we are dealing with the noun “liveness”, I also feel it might be important to consider the noun “liveliness”, described as “the quality of being interesting and exciting”3

Free improvisation, or spontaneous performance, possibly more so than any other approach to music-making, fulfils a vibrant essence of liveness, as scripted or predetermined instructional constructs are abandoned and replaced with unplanned creative direction and decisions. This requires a truly committed state of presence of mind and action, through qualities of being energetic, immersed, and alert throughout every moment of performance.

For with free improvisation, what was not, now is—as moments reveal previously undisclosed possibilities and opportunities through being and through action.

Some notes to consider when reading this text:

I am speaking from the point of view of a disabled musician, performer, improviser and composer, which means that at times I refer to dealing with something specifically (a specificity) related to my disabilities, such as impaired movement or pain. I feel this is something that is shared with most people at some stage, regardless of how they see themselves, as disabled or not.

There is some background writing before the more informal personal observations. For me, although this might provide important thought-provoking insights, I am very much aware that reading long articles can be a drag. So I am happy for people just to skip to my observations and form their own judgements from there. The background can always be read after skimming through the whole article, and is more of a reference.

Introduction

Or, is this the beginning? This could be just the preparation, from where a beginning will take place, the groundwork… What I might refer to when playing as “preparing for practised preparation.” What might be considered more academically as the background.

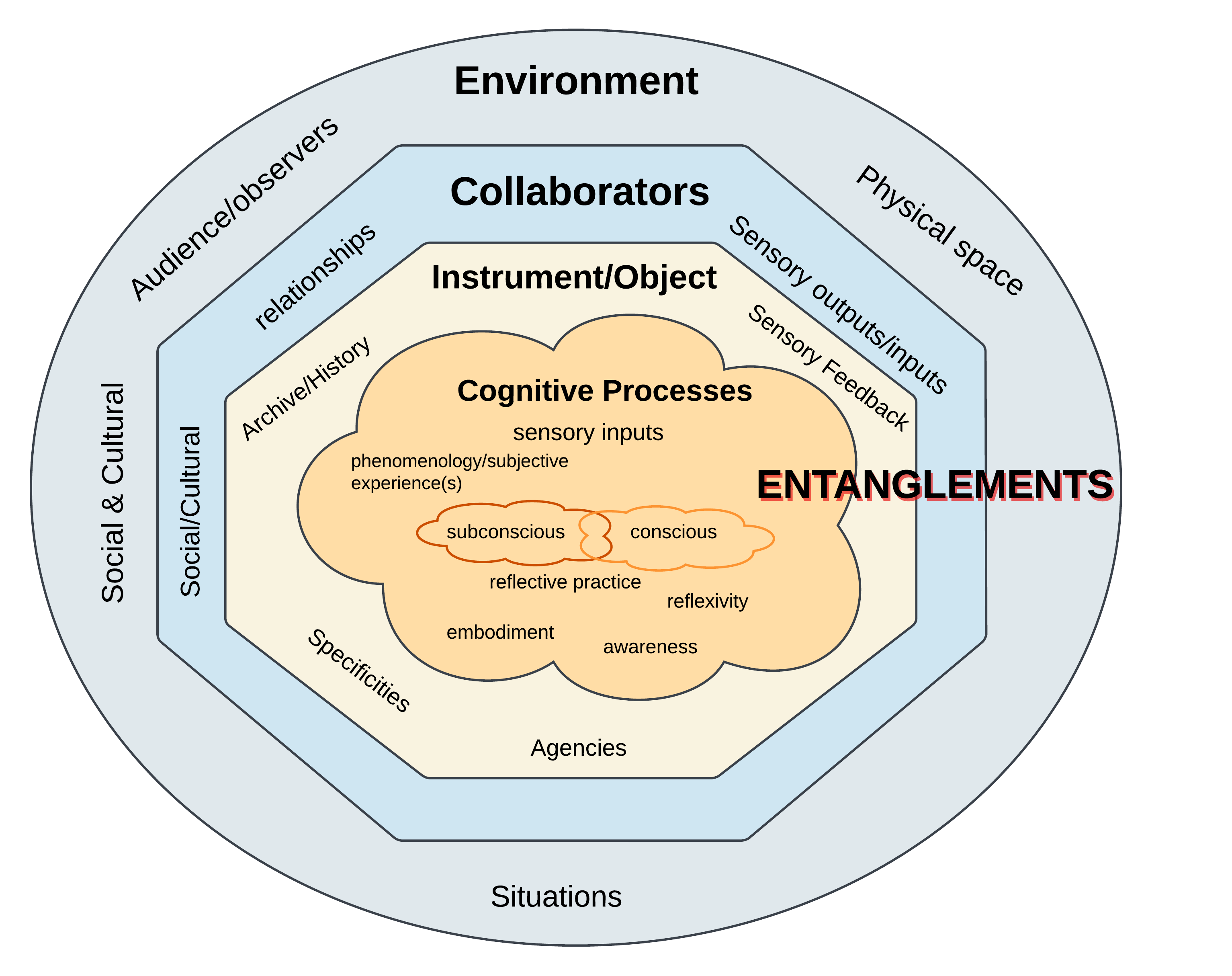

If I were to ask myself how a free improvisation or spontaneous creation is taking place, takes form, constructs itself, finds meaning, and has value, I don’t believe I am in the process of improvising. I am considering the concept of how improvising takes place and what my place is within it. What I know is that improvising is not planned, at least not in the sense that predetermined constructs, specific structures, commands, or other types of instructional inputs directly lead a performance. The performance comes from a constant flow and interaction of and through an ecology, which incorporates cognitive processes, intimate and extended relationships, embodiments, social and cultural settings, and environmental spaces and situations. These in themselves determine for me how an improvisation might take place. So what exists in or creates this ecology for my sense of “liveness”?4 Let me first look to categorize some of the items within the ecology, and then expand from there, defining and identifying links between them. These links are what we could consider entanglements, how we are connected through each part of the ecology, and the elements within it. (At the end of the article, an ideogram shows this ecology visually).

Cognitive processes

Sensory; subjective; conscious and subconscious; reflection and reflexivity

Object/tool/instrument

Specificities; agency; sensory feedback; archival information and possibilities

Artistic or creative practice collaborators

Creative relationships; sensory outputs and inputs; feedback—dialogue and interaction; social and cultural contexts

Environment

Physical space; audience and observers; situation(s); social and cultural contexts

The Instrument

I would like to begin with the second category, and how we might consider our instruments. Tom Jackson (2020) questions whether or not instruments are about the past, creating the sounds they were designed to make, a representation of that history—or are they there to invite exploration into the possibilities of future sounds? Jackson considers that instruments are artefacts/objects, archives containing musical history, possibilities, and futures. They are part of the entanglements of our musical ecology involved with the act of performing or creative practice. Jackson highlights the thoughts of Pauline Oliveros, Steve Lacey, Derek Bailey, Edwin Provost, John Butcher, Evan Parker, and Peter Evans who consider “their instrument as a text (a collection of instructions), a site of ideas and an influence on the imagination” (pp.1-2). Simon Waters, in his article discussing our entanglements with musical instruments, suggests that instruments, as part of social constructs, are used to “sense out, test and probe the possibilities of self-other relations in dynamic, mutually-engaging and often playful and improvised behaviours” (2021, p.1). For me, this relates to the instrument being an integral part of my live creative process within a free improvisation. I can consider the instrument or object not unlike a score with its own rules, instructions, or specificities creating entanglements: a force that directs and invites creative responses, interpretations, and complications. How I relate to it and embody it within an improvisation is crucial; my intentions and its responses with and against me drive the direction of each moment as I strive for what Nijs et al. (2013) terms “functional transparency”5. This is where the object, in this case, a musical instrument, disappears from my consciousness as I go about the task of creating in the moment of a spontaneous composition. This is crucial to being actively involved in the improvisation and its processes. As Tom Jackson claims—related thoughts are expressed by Ruby Solly in He Iti Te Oro Ne He Nui Te Kōrero: Indigenous Communication Through Sound, and Celeste Oram in Learning Your Instrument: A Method-Manifesto—not only are we establishing a relationship with an object that drives our creation, but a relationship with an entire history, a community, a social structure that exists within the object or instrument. This very object is not only integral to, but is one of the centre points of determining the “liveness” of an improvisational performance. It is the link—the bridge—between the entanglements of and through the performance ecology. So what is involved in creating these links?

Cognitive Process

In this space (linking mind, matter, time, and space), I go about the process of connecting myself with my instrument, the environment, and my ideas. A formation between conscious and unconscious thought produces ideas, engages through responses and initiates creative actions. For, as Von Hartman (2002) states, an idea does not exist, cannot be measured, or is not fully realised, unless it is put into action. When putting my ideas into action throughout the moments within a spontaneous composition/creation, or free improvisation, I feel I have both a heightened sense of awareness and unawareness. That is to say, I am truly alive and present within each moment, have untamed or unrestricted freedom of thought throughout my creativity, yet am so immersed in the environment or creation of the piece that I am unaware of things outside of it. I am unaware of things that might make me function in this creative process. I am unaware of things that might inhibit my ability to function in other areas of my everyday life. Here, I am referring to pain, restrictions of movement associated with my disability, any problems with my instrument, and issues or problems within the environment. In improvisation, I have managed to overcome these to find an immersive creative space. This is where I could say I have reached what is described as “flow”(Cstlszekihalyi & Nakamura, 2002), and referred to above by Luc Nijs as functional transparency. If I am lucky, and everything works to stay engaged through the performance/creative ecology, I might maintain this state throughout the entire piece. If not, I may experience this state from one moment to the next, or in a series of moments as part of a section of the piece. Here, being reflexive is an important part of having cognitive flexibility: the ability to adapt throughout the creative process of spontaneous music-making, composition, or free improvisation. This cognitive flexibility shifts between different states of awareness, dealing with what presents itself as either opportunity or issue, and assists with maintaining a link between my mind, my object/instrument, collaborators, and the wider environment, or what I am referring to as the performance/creative ecology.

Collaborators

Throughout a performance, I feel I am constantly negotiating a relationship between myself and who I am performing with. This can come as a dialogue of creative material that we could consider either accepted or declined at any moment. Through being accepted, it might be engaged with in many ways, interacted with as a form of dialogue, supported, developed, counterpointed, or even purposefully played against or ignored. As I write this, I now consider that all material at some level becomes part of the accepted category; it is hard to decline something that exists in a relationship with you. As free improvisation can be considered egalitarian, our relationships are forged through undisclosed intentions, they develop informally, unrestrained, unrestricted, uncontrived, and explored boundlessly, yet paradoxically define the group's boundaries. This has been discussed in conversation and written about, but can be hard to qualify how it is egalitarian, and what are the principles behind it. Writing such as Ritwik Banerji’s Free improvisation, egalitarianism, and knowledge (2023) raises some questions around how we might think about this, and Derek Bailey’s excellent book Improvisation, describes in conversations some of the aspects around performance practices, group interactions, social and cultural environments and situations, that might provide links and values aligned with egalitarianism in collective spontaneous creativity. Rados Mitrovik (2019) wrote an interesting article comparing approaches and philosophies around group improvisations between Cornelius Cardew and Frederick Rzewski. Another great read is David Toop’s Into the Maelstrom (2016), which discusses many practices exploring freedom of expression through freedom of thought, and how interactions between artists and culture are defined. There is a particular focus on spontaneous creativity, and its relationship to cultural practice(s), language and societies. Toop states that “improvised music is a collective experience, and making event that can only evolve into a single viewpoint by losing the provisional character of its origination” (p.70). He references Evan Parker who considers that musicians are diplomats, “unlike solitary artists, they have to live with each other”. Toop goes on to point out the complexities around musicians living with each other, and how these contribute to oscillation between “conscious awareness of group activity, a highly concentrated sense of self and the repercussions of external forces and other timeframes, all of which contribute to the generation of a music” (p.70).

And so, my cognitive processes—how I relate to creating actions with my instrument in the moment—interact with my collaborators through a feedback loop. This feedback loop is based on our creative responses to each other, which, with our social and cultural relationships, contribute to the creation of situations and entanglements across the performance ecology.

Environment

The first point I would like to make is that I consider the collaborators part of the environment, but more immediate to me in my creative moments. The wider environment involves elements such as the physical space, its reverberance or sonic qualities, and spatial layout. It also includes the observers or audience that, through their presence, provide input to creative responses at either micro or macro levels. They also impact the physical space and its sonic qualities. This environment, which is shared in the process of creating a spontaneous piece, carries with it social and cultural contexts providing the situations that surround and determine our interactions into play. These situations are brought by each individual, performer or audience member: how they react or respond in the space and how the group might interact as a whole. This environment, and the situations, can be extended to all the communities that support, are interested in, or knowledgeable about the creative direction (or, for want of a better word, genre) that is being explored.

So, how do these ideas that I have formulated from what I have described above relate to my own creative practice and what I consider important? Now that I have laid the foundations of some background and a formal setting, I’d like to move to an informal style, a more free-flow approach: to place my ideas and concepts on the page. Some may resonate with you, some you may find questionable, and others you might strongly debate or disagree with, and as this is a personal account, it should be open to all perceptions and discussions.

Now am I practised and prepared for the beginning? How to start? It seems this all started some time ago, but where is it going to go, what am I looking for, adding, developing, ignoring or missing? We have got to this point, but do I draw only from what I know? Or should I start with something new?

Looking back, what has happened? Have I missed something? Could I put it across in a better way, in a better moment? What have I prepared for? This? I can’t help but reflect and draw from the past

From what I know:

Below are points, proposals, or provocations, or probes I propose important for the actuality of my existence within an improvised performance to materialise:

What I consider important

Communication is key

Listening

Responding

Introducing ideas/creative material

Relationships

Internal/subjective/conscious and unconscious

Close/medium /instrumental/embodiment

External

Collaborators

Audience/observers

Environment

Bring to each performance

No expectations

Prepare practised preparation

Commitment to each moment

Person

Situation

Be flexible and reflexive

Engagement: be cognisant of internal processes and external connections and inputs

Address any ‘interruptions’ between mind, object, and actions

Stay aware of how introducing material, responding to material, and external responses (from fellow collaborators, venue environment, audience/observers) work in the piece

Develop and enhance the flow of subjective perceptions and cognitive processes toward creative intentions, actions, and responses

Connection with instrument

Physical/haptic/tactile

Is the instrument in tune:

With itself?

With me?

Me with the instrument?

With the collaborators?

With the environment?

Connection with collaborators

Awareness of environment

Philosophy

Ontology — reality, existence

Our presence or being with objects and spaces

For improvisation, the existence of the performance in motion, a unique entity, or existence

Epistemology

Gathering learning from learning

Experience through experience

Creating by creating

Paradigm

Framework for creating, involving:

Tools/objects/instruments

People/collaborators

Spaces/environments

Beyond musical notes, these factors, concepts, processes, and physicalities determine how our improvisations are shaped. Our starting points refer to and reflect situations, gather and provide moments, momentum, and insights into possibilities. Reflexivity and cognitive processes from my conscious and unconscious subjective experiences are linked through entangled relationships between objects, people, environments, and sensory materials or inputs that drive the structure and determine developments and the overall outcome of the performance.

Beware of SELF-DETERMINED DIRECTION or INTERNAL DESIRES… you’ll lose… what?

Opportunities

Engagement

Fulfilment/Creative sustenance

Development

Connections/Relationships

So is that all? Is that it? Where is the ending? Was that it? Did I miss it? Next time… next time

What is this? Is it any good? Why am I even asking myself this NOW—of all times? Was I doing something? What was it? What’s everyone else doing? I should be listening with my eyes as well as my ears! Look for the sound and its source… listen, interact/respond, then develop. Hold on! Hold on to that, it will/might fit if we give it a chance. Don’t throw everything away too quickly, unless it really is rubbish…

Play with time, not in time or tempo. Embrace the fluidity of flexible time as it stretches and contracts through pulse and momentum. Let moments dictate moments, momentum through… whatever… happens…

NEXT

There is no hierarchy here. Egalitarian principles are the only way we truly create something worthwhile, together, though. Is that Unity? Or coexistence? Sonic cohabitation?

Skills, tools, techniques

Lately, I’ve been reflecting on how I want to engage with an instrument in order to be immersed in an improvisation. This has come about through considering the differences between how I’m able to play instruments since my accident and my disability, and before? Since 2004, I’ve had a spinal cord injury which has left me unable to move my hands and has impacted the range and motion of my arms. Being in a wheelchair considerably compromises my ability to access or move into, be with and around, or hold an instrument.

The reason I mention this is that reflecting on playing before my accident and afterwards has given me an insight into the skills and techniques I had worked on. Those skills and techniques, along with the instrument, were my tools to engage in improvisational processes and creative practices for spontaneous composition, and ultimately—liveness. What’s apparent to me now, reflecting from the position of somebody disabled, without easy access to playing instruments, is that there are fundamental skills I can consider important to my music-making or creative practice.

Freedom of Expression in Instantaneous Composition

Part of this reflective practice has led me to listen to recordings from my studio, where every week collaborating musicians and I would record sessions of improvised music. Those sessions were from a timeframe circa 2002 to 2004.

What became of interest to me is that my ability to express ideas and develop material spontaneously and instantaneously came from a mixture of techniques and skills I had developed and was still working on developing. They included using improvised melodies, extended techniques, and sonic tonal elements for producing the material to develop through interactions with other collaborators, the environment, and cognitive and subjective processes.

Especially considering the reflexive nature demanded when improvising, I now consider the following as essential for my access to creating an instrument that provides the ability to improvise freely:

Personal Requirements

Skill level:

Accuracy

Speed (between cognitive reaction, creativity, and action through responses)

Engagement

Fluidity

Flow

Stamina/duration

Ability to access a range of tonal palettes and notes

The ability to “access” all possible areas of the instruments provides connection and communication with/between:

Phenomenological/subjective experiences

Cognitive processes

Ecological or environmental influences

The “liveness” involved with improvising is both an experience and an expression of many processes, all interacting in various sequences. We might consider those from the internal cognitive processes and our senses to object/instrument relationships, collaborative communication, environmental awareness and feedback, social and cultural connections and situations. All these categories and processes are entangled through the moments of our creative practice.

Currently, I’m considering that having reflexivity through those processes and interactions might help an understanding of my place in each moment of the situation. Being reflexive suggests an immediacy of action, a response from within a moment. This differs from the practice I mentioned above regarding reflecting on my playing before my accident and the comparison with my post-accident disability. Instead of taking a lot of time to consider past experiences, knowledge, and outcomes, and bringing them into the present practice/experience or construction, then reflecting and considering changes, and alternatives for the future, I do this instantaneously. Immediately. Both reflective practice and reflexive practice draw from how our subconscious and conscious minds perceive experiences, and how they engage with each other in an internal dialogue, investigation and action. It's just that reflective practice dedicates more time to plan future actions from reflection, whereas through reflexive practice or reflexivity we immediately respond in action. I think there is, therefore, more of a sense of ‘liveness’ in reflexivity than in reflective practice.

Our past experiences and knowledge have already been practised. Our immediate thoughts and constructions are being explored through that ingrained understanding along with the inputs from our histories, social and community relationships, collaborators, senses, environment, and situation. Our future will present itself as our present unfolds but the key is: how open are we for our engagements in the present?

How present am I? How much am I listening, watching? How aware am I of the development of this situation? Am I pursuing my own desires beyond or above communicating with others?

The future or development of the piece is determined by this presence in the moment as it pushes and pulls towards possibilities. What are the possibilities, though?

Building – towards climax

Reducing/decreasing/deconstructing – towards more space or silence

Transition – alterations and development or deconstructing material towards change

Ending – the ultimate result, stopping when the time has come when the material has been exhausted or can be left

Of these five points, the ending is the hardest, the easiest to miss, for it presents itself fleetingly, so briefly at times, it’s gone before it can be actioned. But how do we action it?

Could it be awareness of the moment, through honing my reflexive practice, will help recognise this taonga? For an ending is pure gold, a treasure, a moment in an improvisation which is the most powerful. It is held in the hands and minds of all the performers and no one owns it. It is a collective agreement, yet unspoken: it is decided through a unique dialogue.

The opportunity to create an ending is obscure but simple.

STOP FUCKING PLAYING!

TAKE YOUR HANDS OFF THE INSTRUMENT!

If somebody else keeps going, let them. It’s a solo, the piece will end in a solo…. if I start playing again, a new ending needs to be found and we have lost a precious moment.

The questions we can be left with are:

Was that the end then? Or, was it somewhere else? Before? Which before? Now? Too late again

Below is a schema, a diagram, where I have tried to combine and represent the processes I have discussed above into an ecology. This visualisation is not too dissimilar from diagrams which discuss relationships between artists and technologies in an article by Alex Lucas (Lucas et al., 2021). They discuss and produce diagrams that show frameworks for designing instruments for music-making, including: the Music-Making Ecologies perspective (MEP); Human Activities Assistive Technology (HAAT); and Matching Person and Technology (MPT). Although these are musician-instrument relationship-based, they also encompass the wider ecology and music-making, relationships to cultural and social situations and environments. The diagram I have created below focuses on linking through entanglements what I currently consider are the processes, inputs, and outputs that feed, nurture, and sustain me throughout an improvisation. The interaction of these entanglements happens from moment to moment, in synchronicity, instantaneously. Blurred boundaries through conscious and unconscious links between each area are, for me, a sign of being immersed yet aware, and actively actioning myself into an improvisation: a practice of constantly probing and discovering through a reflexive creative practice.

References

Bailey, D. (1993). Improvisation. Da Capo Press.

Banerji, R. (2023). Free Improvisation, Egalitarianism, and Knowledge. Jazz Perspectives, 2023, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17494060.2023.2249411

Cstlszekihalyi, M., & Nakamura, J. (2002). The Concept of Flow. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 89-105). Oxford University Press.

Jackson, T. (2020). The musical instrument as archive in free improvisation. ECHO, 5. https://doi.org/10.47041/YHHQ3201

Lucas, A., Harrison, J., Schroeder, F., & Ortiz, M. (2021). “Cross-Pollinating Ecological Perspectives in ADMI Design and Evaluation.” International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression, April 29, 2021. https://nime.pubpub.org/pub/d72sylsq/release/1

Mitrović, R. (2019). Improvised music as socially engaged art: Poetics of Cardew and Rzewski. New Sound - International Journal of Music, 54, 109-121. https://doi.org/10.5937/newso1954109M

Nijs, L., Lesaffre, M., & Leman, M. (2013). The Musical Instrument as a Natural Extension of the Musician. In M. Castellenga, H. Genevois & J. Bardez (Eds.), Music and its Instruments (pp. 467-484), Editions Delatour France.

Oram, C. (2022). Learning Your Instrument: A Method-Manifesto. BLOT: A Journal for Music, Sound and Performance in Aotearoa. https://www.blot.online/journal/1/learning-your-instrument-a-method-manifesto/

Solly, R. (2022). He Iti Te Oro He Nui Te Kōrero—Indigenous Communication through Sound. BLOT: A Journal for Music, Sound and Performance in Aotearoa. https://www.blot.online/journal/1/he-iti-te-oro-he-nui-te-k-rero/

Toop, D. (2016). Into the Maelstrom: Music, Improvisation and the Dream of Freedom: Before 1970. Bloomsbury Publishing USA.

Von Hartman, E. (2002). Philosophy of the Unconscious. Living Time Press.

Waters, S. (2021). The entanglements which make instruments musical: Rediscovering sociality, Journal of New Music Research, 50(2), 133-146. https://doi.org/10.1080/09298215.2021.1899247

Acknowledgements

I’d like to acknowledge the following people for assisting me so generously in the creation of this article: Antonia Barnett McIntosh & Samuel Holloway from BLOT for their tireless support, feedback, and editing while putting this article together with me. My supervisors Fabio Morreale, John Coulter, and Sean Kerr, at Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland, for constantly pushing my research and creative practice. All my friends and fellow collaborators at Vitamin S, the Audio Foundation and beyond for all the opportunities to create performances, discussions and more. And Dairy Flat Country Women’s Institute for believing in me, and starting me on my creative journey.

Notes

1

Definition of “Liveness,” Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 13 January, 2024, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/liveness.

2

Definition of “Liveness,” Collins English Dictionary. Retrieved 12 January, 2024, from https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/liveness.

3

Definition of “Liveliness,” Cambridge English Dictionary. Retrieved 10 January, 2024, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/liveliness.

4

Liveness is a noun describing a state of being, a quality of energy, and/or enthusiasm. For the purpose of this writing, I am applying it as a term describing a sense of engagement in spontaneous creative practice within the ecology of that particular creation.

5

Functional transparency refers to when an object, a tool—in this case and the musical instrument—becomes like an extension of our body, another organ. It disappears from our consciousness and the borders or boundaries between ourselves and the instrument become blurred or fuzzy. See Nijs et al. (2013).

After winning the Country Women’s Institute Cup, aged 5, for flower arranging, animal/bird from nature, papier mâché pig, music and sound became Andrew McMillan’s creative focus. Based in Tāmaki Makaurau, Andrew performs and organizes improvised music events, and is researching Accessibility in Music-Making at Waipapa Taumata Rau, University of Auckland.